Gamification is a hot topic. Missed it? On Google Trends it first appeared as a blip in late October 2010 and then took off in January so quickly that it appeared on NPR’s Weekend Edition in March. Investors seem interested, and it already has a sold-out conference and a fast-growing list of agencies that will help you “do gamification.” You can even join a quest to become a gamification expert.

As I dove into some reading, a framework emerged that helped me understand gamification generally, and also specifically how (or whether!) to think about it in relationship to projects I’m working on at the moment. This framework also helped to put all the examples and criticisms into a context I could get my head around.

Defining Gamification

Gamification, according to Wikipedia, is:

[T]he use of game play mechanics for non-game applications… particularly consumer-oriented web and mobile sites, in order to encourage people to adopt the applications. It also strives to encourage users to engage in desired behaviors in connection with the applications. Gamification works by making technology more engaging, and by encouraging desired behaviors, taking advantage of humans’ psychological predisposition to engage in gaming.

In other words, make the stuff you’re building engaging so people do what you want, or think about ways to make them want the same things you want. And this is the breakthrough bit: the stuff you’re building doesn’t have to be a game to be fun or engaging—anything can be fun or engaging!

A Framework for Understanding Degrees of Gamification

As the critics point out, some gamified products are just poorly executed. Just because you saw something in a game once doesn’t mean it’ll be fun in your product. But I think that most of the critics of gamification fail to take into account the wide range of execution that’s possible. Gamification can be applied as a superficial afterthought, or as a useful or even fundamental integration. To tease out some differences and to think about how to implement gamification, we at DesignMap have started to put together a framework:

- Cosmetic: adding game-like visual elements or copy (usually visual design or copy driven)

- Accessory: wedging in easy-to-add-on game elements, such as badges or adjacent products (usually marketing driven)

- Integrated: more subtle, deeply integrated elements like % complete (usually interaction design driven)

- Basis: making the entire offering a game (usually product driven)

Cosmetic Game Elements

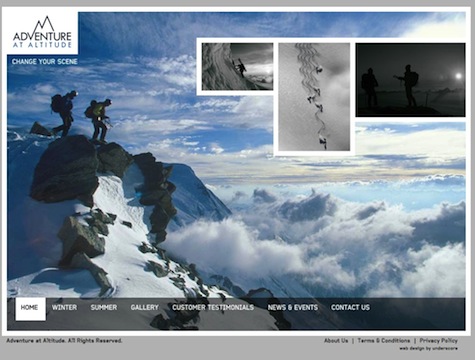

Examples that fall into the cosmetic category abound, especially in shopping, with the use of large photographs that are reminiscent of the immersive graphics available in popular video games such as the Call of Duty or Halo series. The purpose of this in games is to immerse the player into a believable experience. It’s also usually reinforced by creating a story around that experience, and the two together create an immersive effect that invites the player to engage. In other applications, the result can fall short unless it’s carefully thought through.

The Adventure at Altitude site uses a large photo background it looks like it could have come right out of Cursed Mountain or Uncharted2.

Uncharted 2

You could be choosing this Chrysler 300 from the armory of Halo Reach

The Halo Reach armory

Almost too right-on-the-nose, the Prada site includes comic strips

There are also more sites using fun or playful copy. With the recent release of Portal 2, it’s hard not to think of the Portal AI’s promise of cake.

iMeet is dusting your cube, suggests that you take this time to fix your hair, and is warming up the room.

Dropbox recommends a Snickers bar.

Easter eggs also fall into this category.

YouTube’s snake Easter egg

Accessory Game Elements

Gamification in the accessory category is the most common, and draws the most criticism from the gaming community for having no value beyond pure marketing pull. Some of the gamification services provided by companies such as BigDoor and Bunchball fall into this space. Their services provide explicit rewards such as points, levels, and leader status. The fact that external companies can even provide “gamification solutions” to other businesses speaks to their fundamental add-on-able-ness.

Bunchball addresses a laundry list of gamification “mechanics” and needs

Other examples of accessory gamification include tacked-on game elements such as newsgames like Huffington Post’s Predict the News. Poorly performing leaderboards are poorly performing specifically when they’re treated as accessories, and are empty because users aren’t actually motivated to the desired behavior (product reviews in particular seem to suffer from this). Leaderboards that perform well are integrated into the site (see the example in the next category).

Integrated Game Elements

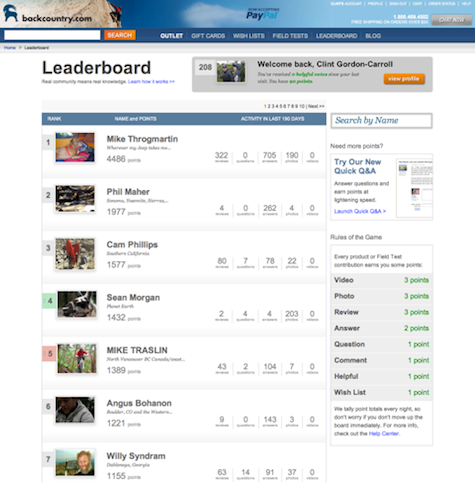

Gamification in the integrated category is subtler, more thoughtfully integrated, and less explicit than the other examples we’ve examined so far. Examples include leveraging a sense of accomplishment and competition for Backcountry’s leaderboard (which is deeply integrated an extension of the company’s DNA of catering to hard-core enthusiasts who are passionate about these products), and Amazon’s top reviewers.

backcountry.com‘s leaderboard

Unlike cosmetic and accessory game elements, integral elements speak directly several types of natural motivations. LinkedIn, Facebook, and Nike use progress meters to entice users onward; the company wants the user to finish, and the progress meters provide a clear visualization of how near they are to a sense of having achieved completion. Sites such as Gilt Group and Daily Candy’s Swirl, or one-deal-at-a-time sites like Woot, use scarcity and competition to drive behavior.

Nike wants you to want to finish designing your shoes

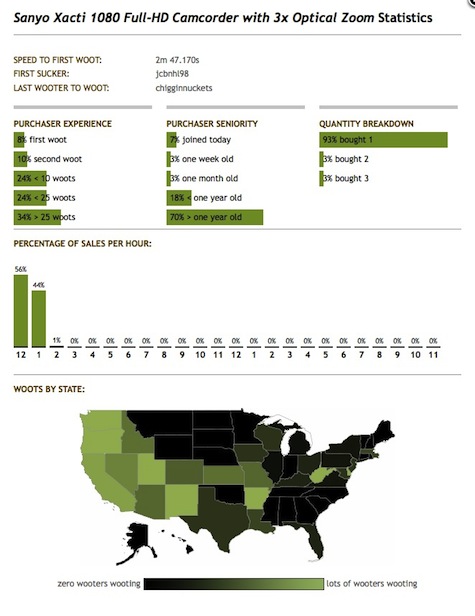

Woot provides detailed information on other purchases

Basis Gamification

In the basis category, activities that weren’t games before have become games. The pleasure people get from playing games is layered onto everyday activities.

Badge sites fall into this category because the whole premise of simply being somewhere is suddenly a game. Badges from sites such as Foursquare, Gravity, Zaang, and Gowalla are all echoes of the rewards provided in video games. Xbox has “achievements,” and the Playstation Network has “trophies.” Wii Sports has a stamp system, although the famous Nintendo game designer Shigeru Miyamoto says:

I’m not a big fan of using the carrots to motivate people to play. I want people to play because they enjoy playing and they want to play more.

Many of the products in the basis category address something that might otherwise be less-than-fun, such as exercising, saving energy, or donating money. Gamification resonates especially with these examples, as these solutions try to make things more-than-less-than-fun. Anyone with kids will recognize this activity, as we wrack our brains for ways to make brushing teeth or cleaning house the most exciting thing anyone could ever aspire to do. Giving to charities becomes more interesting and engaging with products such as Free Rice and Spent. BBC Pinball has some interesting idea management games.

Spent supports the development of empathy and requests donations when the game is over

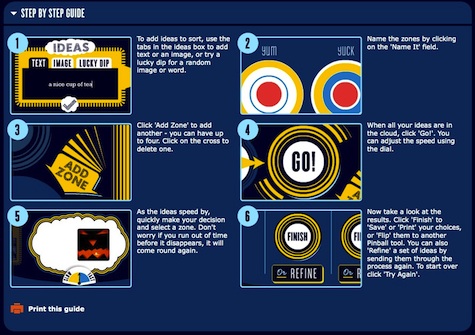

BBC Online provides games to help come up with, sort, and prioritize ideas

Competition shows up in this category too, with sites that help improve personal habits such as stickK, Skinnyo, Healthmonth, and Welectricity.

Welectricity lets users compete against one another and their own goals to reduce energy use

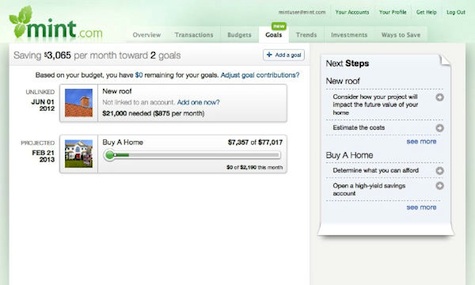

People can save money by punching the pig or chasing Mint’s goals, or cross things off to-do lists with Rough Underbelly, or get chores done with Chore Wars.

Mint helps people set up and keep “score” against a goal

Jane McGonigal is working on saving the world (literally) with her games. A believer in the power of games to motivate, she predicts that UX designers will become “happiness engineers.”

Other Frameworks

As you’re considering how to build gamification (delight, enticement, and interest) into your product, there are some other guidelines or frameworks to consider:

- Gabe Zicherman, chairman of at the Gamification Summit, talks about “SAPS”: status, access, power, and stuff. Gabe’s model may be a game-centric take on Maslow’s broader model.

- In a Mercury News article, Badgeville founder Kris Duggan identified three large categories of behavior that can be influenced through gamification: personal achievement, group motivation, and contextual communications.

- One definition of “game” by Roger Caillois states that games must have all of these attributes: fun, separate, uncertain, non-productive, governed by rules, and fictitious. (It’s interesting to note that most of the examples of gamification I’ve called out meet some five of the six attributes listed here.)

- Richard A. Bartle proposed four types of game players for MUDs: achiever, explorer, socialiser and imposer (if you’re making personas and thinking of focusing on gamification, it might make sense to include their “Bartle type”).

- Nicole Lazzaro and Marc LeBlanc have different but very interesting models on types of games and players.

- When thinking about building game elements into a product, it becomes important to consider a progression of user experience, as opposed to just beginners and experts. See Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s work and this diagram of his concept of “flow.”

- Of course Jesse James Garrett’s framework is useful to re-consider in this context.

Hope for Interaction Designers

Before we pack up and leave the field for the game designers, it’s worth considering what’s really going on in the last two levels of our model, integrated and basis: the enticement of people into an action to support their own goals within a product. This is the space where interaction design plays nicely, remembering all that we’ve learned from our years of persona development and that no one wakes up in the morning hoping to fill out a form that day. Instead, we empathize with people, and remember that they have higher goals. We use our skills to create delightful interactions that entice people to move forward within our sites. This is the stuff we’ve been doing forever. As Vitruvius said (loosely translated), “Good design has three things: stability, usefulness, and delight.” Interaction designers are perfectly positioned to start delivering this kind of delight.

More Reading

“Gamification” returns 847,000 results on Google, but we found some particularly clear, helpful, and super-smart thinkers if you want to learn a little more:

- Stephen Anderson, The Art & Science of Seductive Interactions

- Sebastian Deterding, Just Add Points?

- Dan Saffer, Gaming the Web

- Amy Jo Kim, Beyond Gamification

- An interesting example of using a game to facilitate sharing information about road changes