Save

This article refers to a talk I gave at the June 2021 edition of the UX writer conference, called “Every Brain Is Different: Neurodiversity’s Significance for UX Writing and Content Design”. I feel like we’re onto something here, so let us make the most of the momentum to take a step back and reflect (thanks again Steven Wakabayashi of QTBIPOC Design for reminding us all to do so in his own talk “Designing for equity” at the same conference).

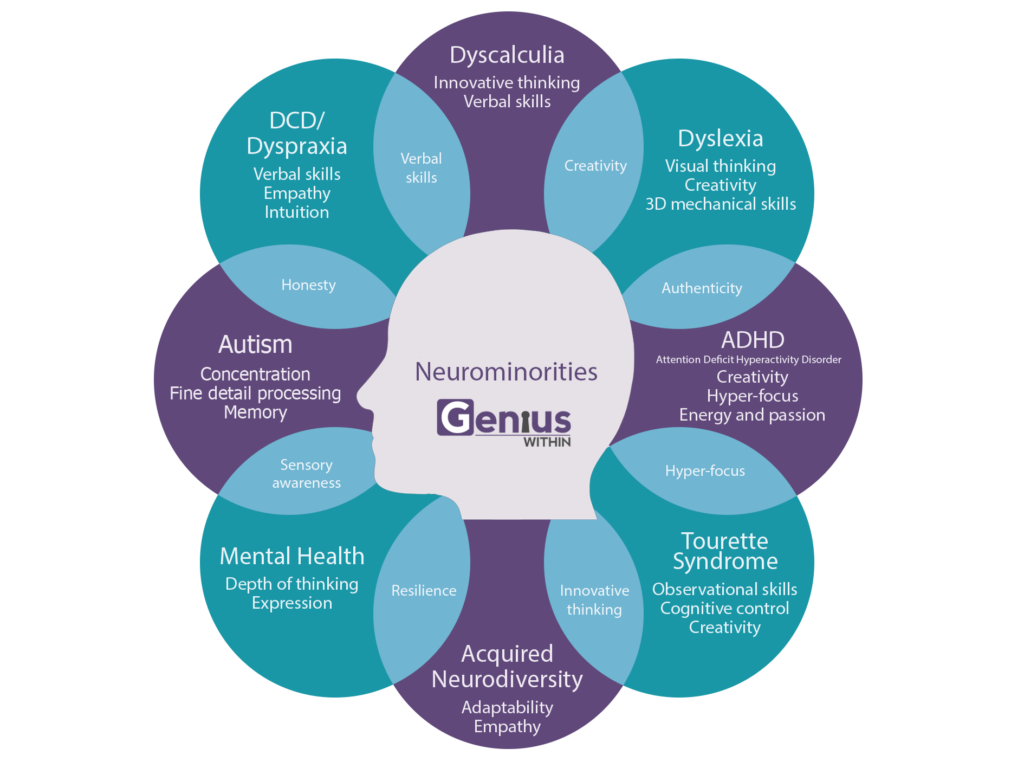

1 in 5 humans ‘has a difference in their brains’. Of course, each and every brain is nothing like the other, but in this case, neurodiverse or neurodivergent brains make up this 20% which we know of. Plus, there can also be a whole rainbow of differences. I am writing “differences” to be as plain as possible, not only to keep it neutral in its meaning.

Since terms such as neurodiverse, neurodivergent and on the spectrum still need to be claimed or reclaimed by those people themselves. Not to be determined by psychologists or scientists. Leaving naming and wording everything to scientists doesn’t mean it leads to great things — as the fun Netflix show “Special” recently educated me about the origin of the term Asperger’s for a certain type of autism.

Words matter, visibility matters as well

Being respectful and mindful, whether someone wants to be called autistic or dyslexic, is just like you would address a person with depression not as a “depressed” person. By doing so, you would make their condition a fundamental part of their personality, while they are so much more.

To catch up with all the brain differences belonging to the umbrella terms of neurodiversity and neurodivergence, I will include a visual from Genius within to make it more memorable:

What’s in it for you, if you keep on reading?

- Find out about my research findings to showcase neurodiverse human needs in your work environment,

- take away real-life data from the participants of the survey, some of them are UX (writing) professionals themselves.

- Learn ways to convince stakeholders to opt for all-encompassing inclusivity, diversity and equity in design.

- Create copy for everyone.

- Think of people on the spectrum, who are so often overlooked, since their differences from the norm remain invisible, oftentimes even to themselves — include them in your design and thought processes.

Additionally,

- learn about the research details and take the “Neurodiversity and UX writing” survey, too, if you are on the spectrum too, or know people who are.

- view the data on my live Miro board.

- read more about neurodiversity and UX in the Medium articles I share.

Invisible to us, invisible to them

When talking about claiming some part as your own identity, first, you have to be aware of that difference in your brain. But many people on the spectrum of neurodiversity go undiagnosed through life — struggling with self-hatred and shame because they are constantly being treated differently by their environment without them knowing why.

Whether your self-diagnosed or officially diagnosed is not as important as whether you feel relief to finally being able to “call it by its name”. Also, a diagnosis of some conditions such as Tourette’s or anxiety can make a huge difference, because then you are able to get help from professionals or even medicine.

Why neurodiverse needs matter in UX design

In a truly inclusive design approach, you aim at full inclusion, right? You never know what goes on in the brain of your audience, or do you? So why overlook 20 per cent, most likely to be a much larger chunk of humanity?

If stakeholders argue that their meticulously carved out persona in high-paid, successful roles “are not like that”, I would always ask them, why they would think that. Taking ADHD, as an example, shows up in so many very famous, very rich and very gifted people — ranging from musicians like Justin Timberlake, will.i.am and actors as Emma Watson and Liv Tyler over to athletes like Simone Biles, Michael Phelps and Serena Williams. Also, Bill Gates is among those with ADHD. Wouldn’t you want a person like Bill as an investor or client, for example?

Of course, I do not want to idealize or romanticize a brain difference such as ADHD, as the stigma and the shame is still raging and people take their own lives or think about ending it — such as UN speaker Hayley Clarke, who chose to publicly share her struggles with ADHD. Be mindful, that no one has to come out as having those mental struggles, just like no one with visible differences has to.

Why the UX writing discipline needs to sit down and take notes

As we discuss how to write an onboarding copy or look for the perfect CTA to achieve the highest conversion — we also should take the time to look up from our work desk sometimes, and start asking those people who we tend to overlook. They can make our complicated designs easier to access. Why am I certain of that? Because they told me in my research and many designers have been listening to them already before me.

We are part of design and dev teams, so we have a seat at the table and we need to use our voices to do ally work and really be advocates for everyone. If we don’t, we cannot call ourselves user-centred. Since our audience is simply everyone. It may sound like a hard job, such a diversified audience feels a lot to take on and it could feel overwhelming at first— but in all honesty, it turns out to be much simpler as we imagined. Ask yourself while creating:

Is a timer necessary — could it be inducing anxiety instead of a quick check-out we originally were looking for?

Should our latest think piece be a solid wall of text with only one decorative main visual or can we break it up into more digestible paragraphs?

Are our user flows manageable and useful to a variety of people instead of only those who do not need assistance in their daily life to copy with their inner world of emotions?

If you like, read about the real-life data I collected with a survey study for the conference talk: I sent out a set of questions via Typeform to a group of people who had agreed to help my study — the participants either identified as having a different brain themselves or living with a family member who has or are advocates for neurodiverse folks.

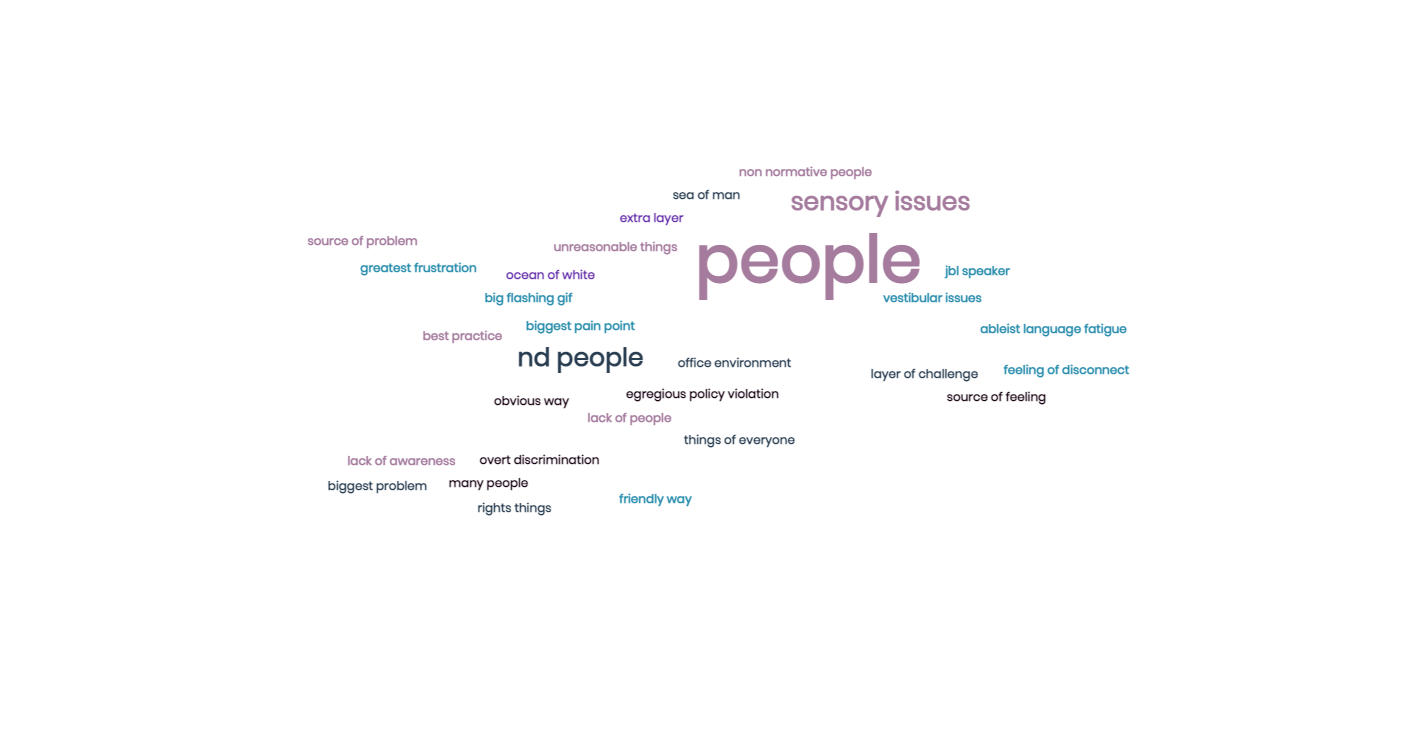

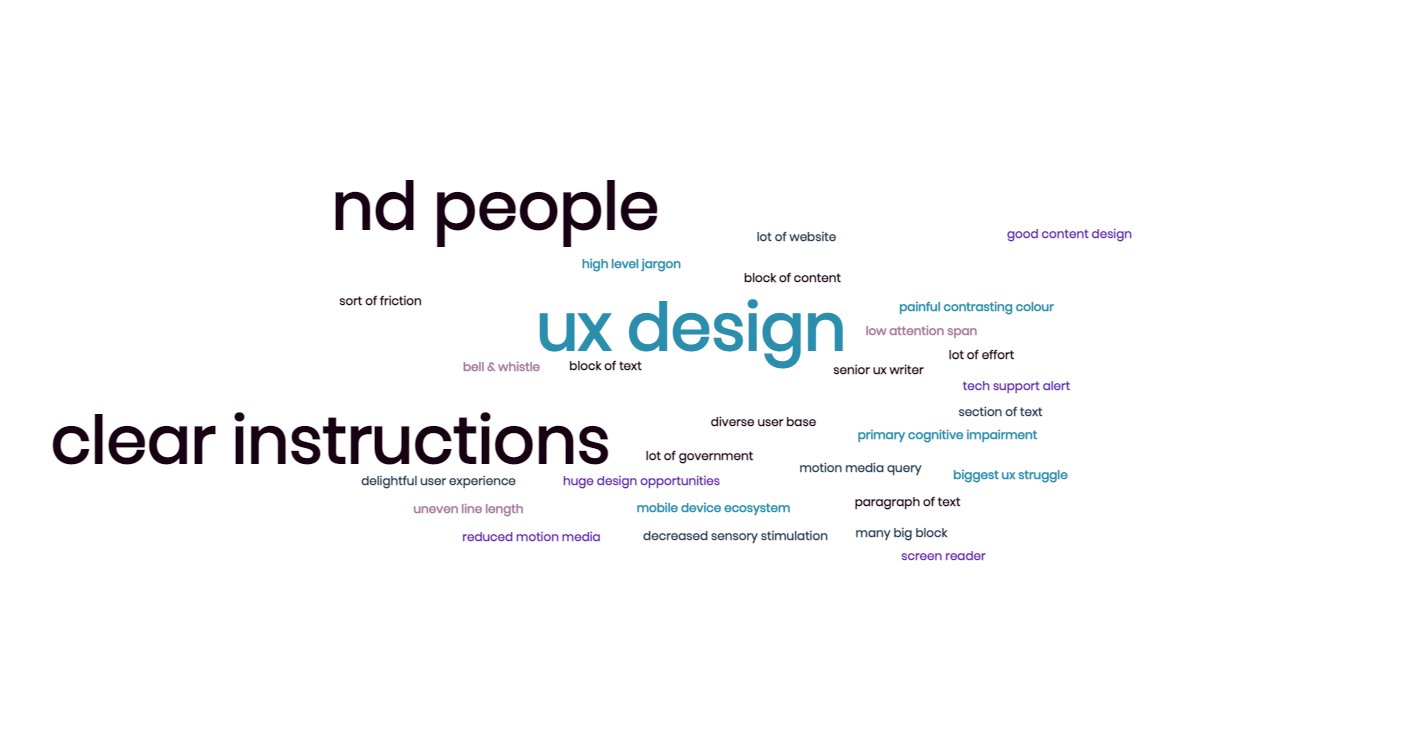

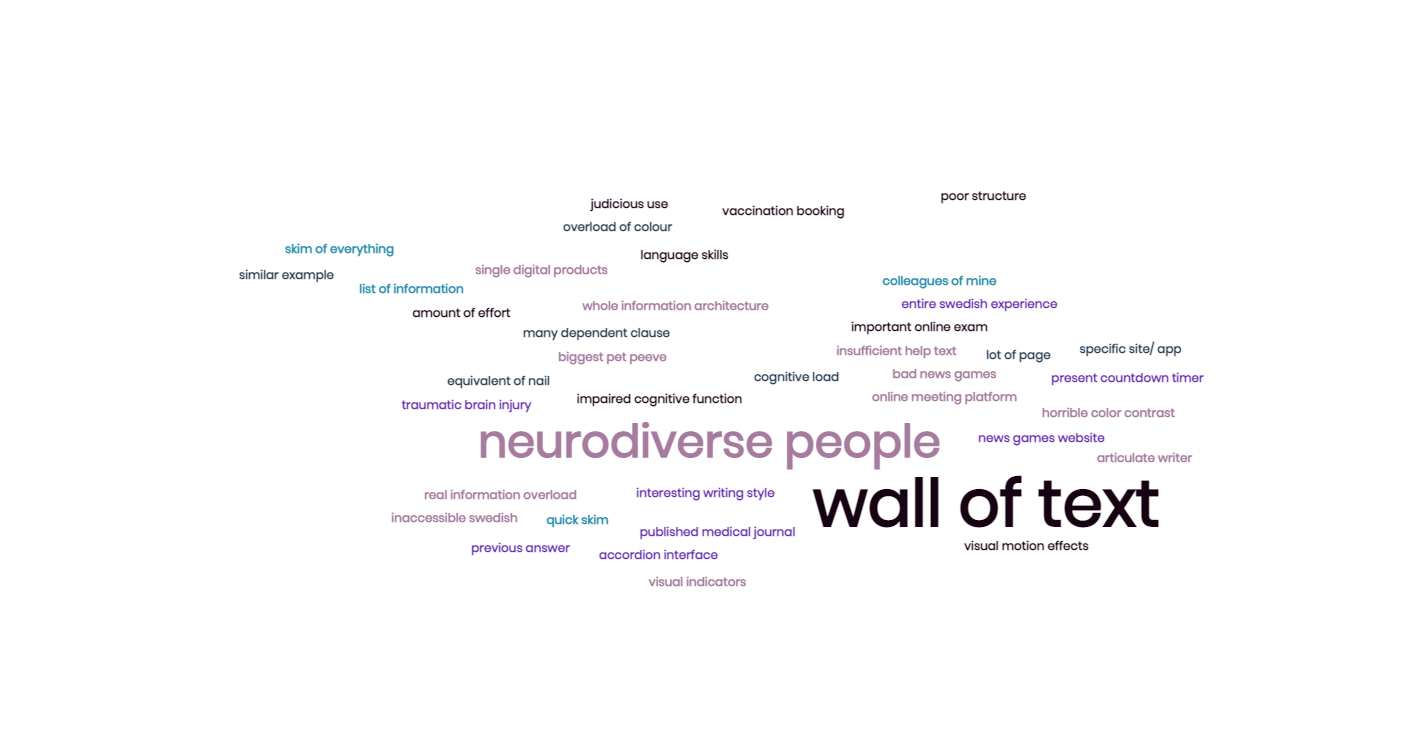

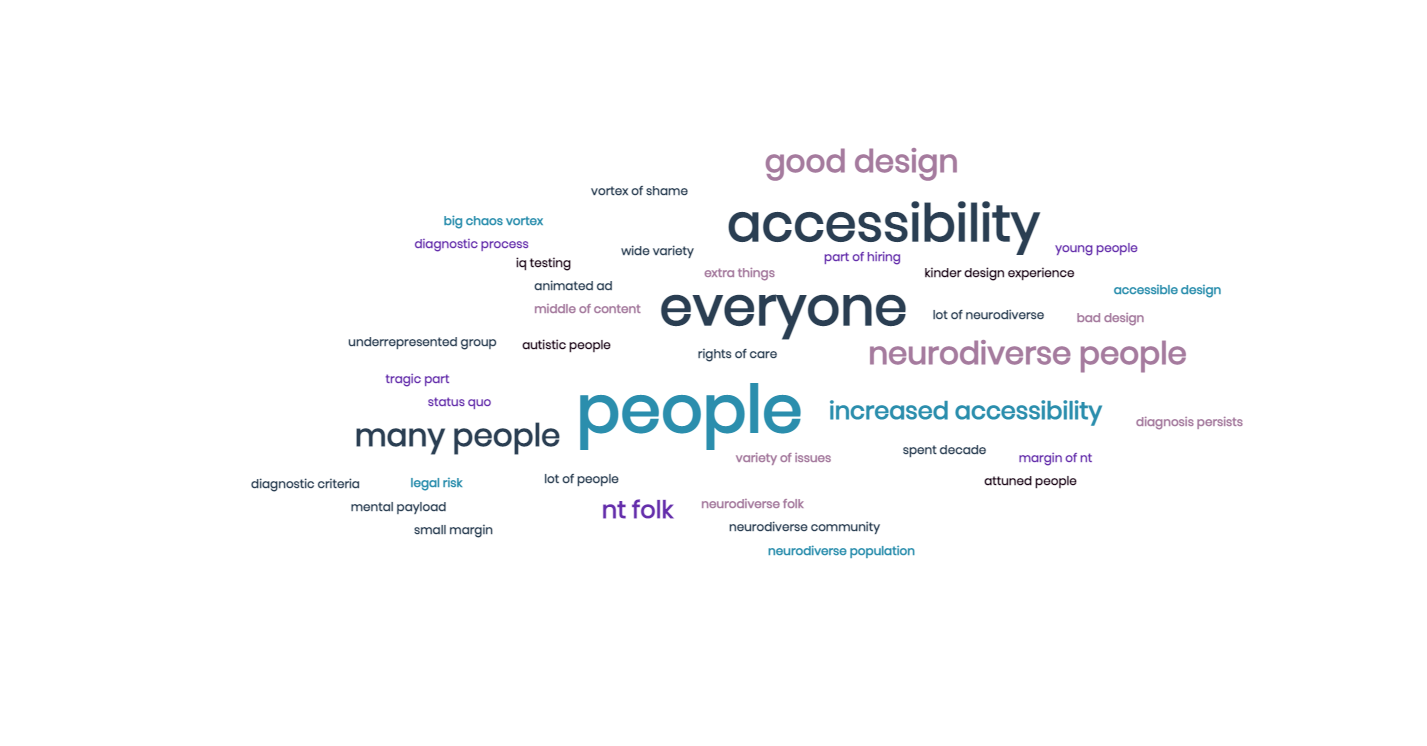

Check out the unabridged answers of all of those individuals who took the time out of their day (thank you!) to answer these top 4 questions on the “Neurodiversity and UX writing” Miro board, or look at the word clouds generated out of these answers right now:

1. What are the biggest pain points of neurodiverse people in general, in the workplace and in their personal lives according to you?

As you can see, lack of awareness, overt discrimination and ableist language fatigue stand out as meta-issues people on the spectrum of neurodiversity are facing. More in detail, office environments are especially challenging in the workplace, which makes working from home a total game-changer for many.

2. Have you encountered any particular goals and needs of neurodiverse people when it comes to user experience design?

All in all, people with different brains are feeling sort of left out of the user experience altogether. Moving visuals, too many bells & whistles, uneven line lengths or too much friction cause trouble for not only those with an extra-short attention span (as seen in ADHD, depression or anxiety, for example). Jargon is a massive pain point, and as we might know from our daily work, people on the neurodiverse spectrum are experiencing the same problems here as all the “normative” folks might be facing, too.

3. Could you tell me about one or more cases of experienced inability to use or read any digital writing because it was inaccessible to neurodiverse people?

Walls of text were mentioned more often than anything else, so here is our main takeaway regarding the inability to complete tasks or simply enjoy a digital user experience. Institutions and the public sector, where accessible UX writing and design is pushed for even by law, are mentioned as being particularly horribly designed and written. Overload of colours, fonts and enormous cognitive load is holding people on the spectrum of neurodiversity back.

4. Why do we need to include neurodiversity when creating an accessible design, especially crafting copy and content?

Ano-brainer to start with: shame and stigma can be reduced, people can feel great about using products and reading content on websites. Increased accessibility helps everyone in the end and we definitely can aim for a kinder design experience, can’t we?

Just getting started with spreading the message

Stay tuned for the next article, featuring more input on the journey we embark on with UX writing seeking equity, diversity and inclusion — such as:

- Which factors should (UX) writers be always mindful of to include neurodiverse needs?

- How well are people on the neurodiverse spectrum thought of in terms of written content for digital products?

Stop writing and start asking

See the Miro board of my talk at the UX Writer Conference (view-only) and let me know your thoughts about how we can craft copy for everyone —please write to me on LinkedIn, since the board is view-only.

If this matter is close to your heart, I would love to hear from you. Also, the “Neurodiversity and UX writing” Typeform survey remains open for now, so more answers are more than welcome and you can stay completely anonymous this way.

Katrin Suetterlin

This user does not have bio yet.

- Before giving a talk at a conference, the author surveyed a group of people. The participants either answered that they have a “different” brain themselves or live with a family member who identifies as neurodiverse.

- By asking four questions on user experience, it was possible to identify major pain points for neurodiverse people, such as enormous cognitive load, jargon, walls of text.

- UX specialists have the power to revolutionize products and make them accessible to everyone, thereby decreasing stigma and discrimination.

Read the full article below to learn more about neurological makeup and how it can impact design.