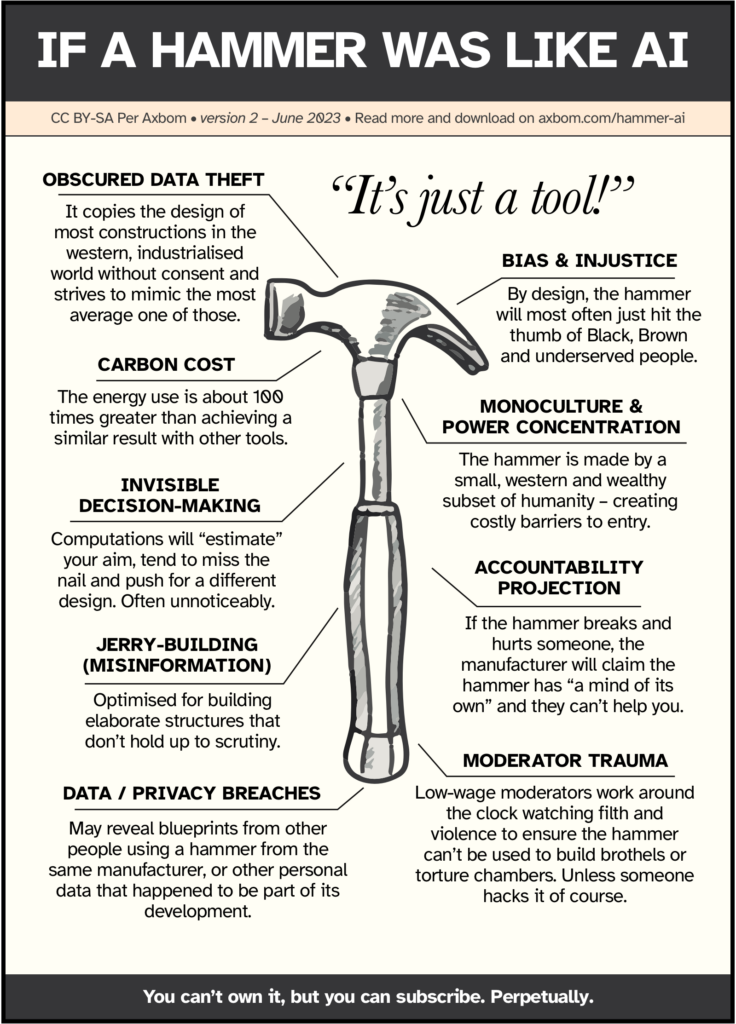

A common argument I come across when talking about ethics in AI is that it’s just a tool, and like any tool, it can be used for good or for evil. One familiar declaration is this one: “It’s really no different from a hammer”. I was compelled to make a poster to address these claims. Steal it, share it, print it, and use it where you see fit.

Note that this poster primarily addresses the features of generative AI and deep learning, which are the main technologies receiving attention in 2023.

Now, that I have your attention, let me take this opportunity to break down what each of the topics in the poster refers to. These and more are also outlined in my infographic: The Elements of AI Ethics.

Obscured data theft

It copies the design of most constructions in the Western, industrialized world without consent and strives to mimic the most average one of those.

To become as “good” as they are in their current form, many generative AI systems have been trained on vast amounts of data that were not intended for this purpose, and whose owners and makers were not asked for consent. The mere publishing of an article or image on the web does not imply it can be used by anyone for anything. Generative AI tools appear to be getting away with ignoring copyright.

At the same time, there are many intricacies that law- and policymakers need to understand to do a good job of reasoning around infringements on rights or privileges. Images are for example not duplicated and stored, but rather used to feed a computational model, which is an argument often used by defenders to explain how generative AI is only “inspired” by the works of others and not “copying”. There are several ongoing legal cases challenging this view.

Bias & injustice

By design, the hammer will most often just hit the thumb of Black, Brown, and underserved people.

One inherent property of AI is its ability to act as an accelerator of other harms. By being trained on large amounts of data (often unsupervised) – that inevitably contain biases, abandoned values, and prejudiced commentary – these will be reproduced in any output. It is likely that this will even happen unnoticeably (especially when not actively monitored) since many biases are subtle and embedded in common language. And at other times it will happen quite clearly, with bots spewing toxic, misogynistic, and racist content.

Because of systemic issues and the fact that bias becomes embedded in these tools, these biases will have dire consequences for people who are already disempowered. Scoring systems are often used by automated decision-making tools and these scores can for example affect job opportunities, welfare/housing eligibility, and judicial outcomes.

No, this does not mean that the hammer has a mind of its own. It means that the hammer is built in a way that has inherent biases which will tend to disfavor people who are already underserved and disenfranchised. AI tools will for example fail to reduce bias in recruitment and contribute to racist and sexist performance reviews.

It’s relevant to compare this topic with a touchless soap dispenser that won’t react to dark skin. It’s not the fault of the user that it does not react, it’s the fault of the manufacturer and how it was built. It doesn’t “act that way” because it has a mind, but because the manufacturing and design process was unmindful. You can’t tell the user to educate themself about using it to make it work better. See also Twitter’s image cropping algorithm, Google’s “inability” to find gorillas, webcams unable to recognize dark-skinned faces, and I’m sure there are many more examples that have been shared with me over the years.

Carbon cost

The energy use is about 100 times greater than achieving a similar result with other tools.

To be fair this is an intentionally provocative number, as OpenAI and other manufacturers will not disclose the energy use of their models. There are estimates claiming that one ChatGPT query costs (in money) 100x more than a Google search, or consumes 10x as much energy. And one ChatGPT session, to get the response you want, can be estimated at 10 prompts.

But in the end, there are many examples of things that can be done in more environmentally friendly ways. For example, writing a speech for a wedding. The year 2023 has truly become the year when people trust a computer more than themselves to write words for their loved ones. Another way to write a speech for a wedding is pen and paper and from the heart 😊

What we do know is that the energy required to source data, train the models, power the models, and compute all the interactions with these tools is significant. With this in mind, it is apt to ask if every challenge really is looking for an AI solution. Will consumers perhaps come to see the phrase “AI-powered System” in the same light as “Diesel-Powered SUV”?

Monoculture and power concentration

The hammer is made by a small, western, and wealthy subset of humanity – creating costly barriers to entry.

Today, there are nearly 7,000 languages and dialects in the world. Only 7% are reflected in published online material. 98% of the internet’s web pages are published in just 12 languages, and more than half of them are in English. When sourcing the entire Internet, that is still a small part of humanity.

76% of the cyber population lives in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, and the Caribbean, and most of the online content comes from elsewhere. Take Wikipedia, for example, where more than 80% of articles come from Europe and North America.

Now consider what content most AI tools are trained on.

Through the lens of a small subset of human experience and circumstance, it is difficult to envision and foresee the multitudes of perspectives and fates that one new creation may influence. The homogeneity of those who have been provided the capacity to make and create in the digital space means that it is primarily their mirror images who benefit – with little thought for the wellbeing of those not visible inside the reflection.

When power is with a few, their own needs and concerns will naturally be top of mind and prioritized. The more their needs are prioritized, the more power they gain. Three million AI engineers are 0.0004% of the world’s population.

The dominant actors in the AI space right now are primarily US-based. And the computing power required to build and maintain many of these tools is huge, ensuring that the power of influence will continue to rest with a few big tech actors.

Invisible decision-making

Computations will “estimate” your aim, tend to miss the nail and push for a different design. Often unnoticeably.

The more complex the algorithms become, the harder they are to understand. As more people are involved, time passes, integrations with other systems are made and documentation is faulty, the further they deviate from human understanding. Many companies will hide proprietary code and evade scrutiny, sometimes losing an understanding of the full picture of how the code works. Decoding and understanding how decisions are made will be open to infinitely fewer beings.

And it doesn’t stop there. This also affects autonomy. By obscuring decision-making processes (how, when, why decisions are made, what options are available, and what personal data is shared) it is increasingly difficult for individuals to make properly informed choices in their own best interest.

Accountability projection

If the hammer breaks and hurts someone, the manufacturer will claim the hammer has “a mind of its own” and they can’t help you.

I am fond of the term “Moral outsourcing” as coined by Dr. Rumman Chowdhury. It refers to how makers of AI manage to defer moral decision-making to machines as if they themselves have no say in the output.

By using the word accountability projection I want to emphasize that organisations have a tendency not only to evade moral responsibility but also to project the very real accountability that must accompany the making of products and services. Projection is borrowed from psychology and refers to how manufacturers, and those who implement AI, wish to be free from guilt and project their own weakness onto something else – in this case the tool itself.

The framing of AI appears to give manufacturers and product owners a “get-out-of-jail free card” by projecting blame onto the entity they have produced as if they have no control over what they are making. Imagine buying a washing machine that shrinks all your clothes, and the manufacturer being able to evade any accountability by claiming that the washing machine has a “mind of its own”.

Machines aren’t unethical, but the makers of machines can act unethically.

Jerry-building (Misinformation)

Optimised for building elaborate structures that don’t hold up to scrutiny.

The one harm that almost everyone appears to be in agreement about is the abundance of misinformation that many of these tools will allow for at virtually no cost to bad actors. This is of course already happening. There is both the type of misinformation that troll farms now can happily generate by the masses and with perfect grammar in many languages, and also the type of misinformation that proliferates with the everyday use of these tools, and often unknowingly.

This second type of misinformation is generated and spread by the highest of educated professionals within the most valued realms of government and public services. The tools are just that good at appearing confident when expressing nonsense in believable, flourished, and seductive language.

One concern that does come up and is still looking for an answer is what will happen when the tools now begin to be “trained” with the texts that they themselves have generated.

Data/privacy breaches

May reveal blueprints from other people using a hammer from the same manufacturer, or other personal data that happened to be part of its development.

There are several ways personal data makes its way into AI tools.

First, since the tools are often trained on data available online and in an unsupervised manner, personal data will actually make its way into the workings of the tools themselves. Data may have been inadvertently published online or may have been published for a specific purpose, rarely one that supports feeding an AI system and its plethora of outputs.

Second, personal data is actually entered into the tools by everyday users through negligent or inconsiderate use – data that at times is also stored and used by the tools.

Third, when many data points from many different sources are linked together in one tool they can reveal details of an individual’s life that any single piece of information could not.

Moderator trauma

Low-wage moderators work around the clock watching filth and violence to ensure the hammer can’t be used to build brothels or torture chambers. Unless someone hacks it of course.

In order for us to avoid seeing traumatizing content when using many of these tools (such as physical violence, self-harm, child abuse, killings, and torture) this content needs to be filtered out. In order for it to be filtered out, someone has to watch it. As it stands, the workers who perform this filtering are often exploited and suffer PTSD without adequate care for their well-being. Many of them have no idea what they are getting themselves into when they start the job.

You can’t own it, but you can subscribe. Perpetually.

But isn’t AI a tool?

Yes, it’s fair to point out that AI in its many different service appearances can be considered a tool. But that is not the point of the statement. The word to watch out for is “just”. If someone were to say ” It’s a tool”, that makes sense. But the word “just” is there to shed accountability.

Hence my concern is that the statement itself removes accountability and consideration for the bigger picture effects. Saying something is just a tool creates the faulty mental model of all tools having interchangeable qualities from an ethical perspective, which simply isn’t true.