User narratives are becoming more popular as a tool for experience design. User stories, those discrete morsels of information that give us personas and a sense of action and motivation, are nothing new to design practitioners. User stories are often the trees, however, and the big picture—the context and purpose of the story—is the forest that designers fail to see. Taken alone, it’s difficult to see how the user stories fit into the overall experience.

User narratives link a set of activities together in a seamless flow. They describe specific activities within a work environment, presenting a “day in the life of…” view of the user experience; using a persona to give the experience life, but providing context and embedding experience goals into the story. This narrative is the first step in designing an experience, serving as a framework for creating the flow and the screens that support that flow. Throughout the process, the narrative surfaces requirements and keeps the focus on both the end user and the context of use.

Creating the Narrative

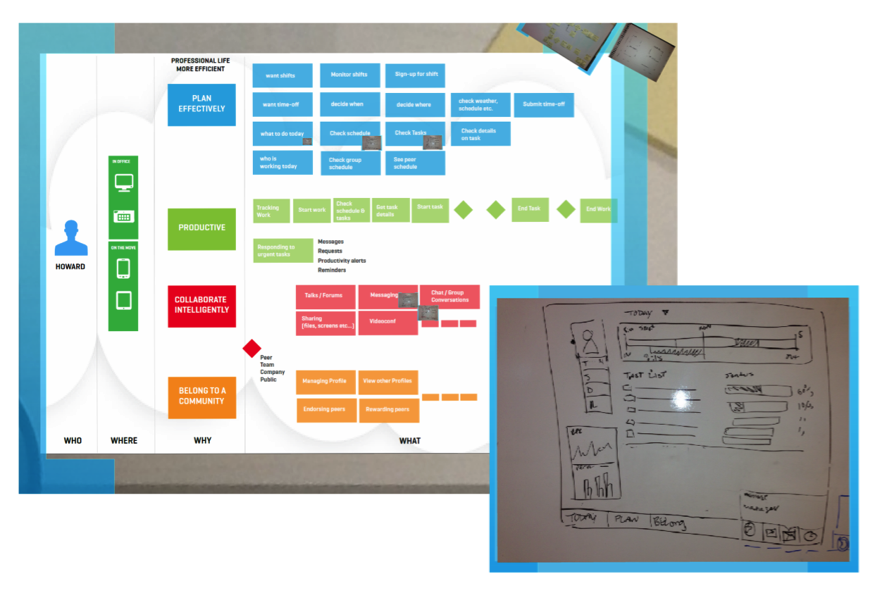

At Kronos Incorporated, an enterprise software company, we recently embarked on a major new initiative to accelerate into the cloud-based market, and the UX team was tasked with evaluating and evolving many of Kronos’s previously held assumptions about their products and users. Rather than using existing products and well-documented solutions as the starting point, the team wanted to start from scratch and encourage new thinking. We decided that a user narrative could encapsulate requirements, personas, use cases, and work context in one short document.

We had developed personas prior to starting the new initiative, and now the product manager and interaction designer focused on three primary users, fleshing out the stories to highlight each user’s goals and actions, and linking them together in a linear fashion.

The narratives focused on the day-to-day actions of the employees using our products, beginning with their time spent prior to their arrival at work. Moving through that arrival and into their experience on the job, we explored the ways they planned, monitored, and executed tasks throughout the day.

We actively removed any “how-to” descriptions, eliminating the solution-oriented language that has a tendency to creep into requirements, and concentrated, instead, on the why. Focusing on the intent and on the user’s motivation allowed us to create an extended user story that did not prescribe a solution, but instead articulated a series of interconnected business needs. Then we color-coded the value proposition within each narrative, visually depicting how customer benefit from our products throughout the day.

The Narrative in Action

The end result was a non-technical, entertaining description of the expected user experience that mapped product requirements to larger business goals, positioning the narratives in a way that resonated with senior management. Howard Edwards, a Home Depot employee and Patriots fan, is the star of one of the narratives. Below is an excerpt:

“After hanging up his coat in the break room, Howard is ready to work on his first task of the day, which is building a Fall Colors paint display. Howard is easily able to “punch in” and record details about the task he is working on. He can also look at information related to the task like: how long the task is expected to take, and what is the average time it has taken employees at other Home Depot stores in the region to complete the task. Howard is excited to see if he can do it faster than his colleagues. He also sees that there is an employee discussion thread related to this task. Howard joins the thread, which says that the stand used to build the display has a faulty leg, and that it has toppled over in several stores. The recommended fix is to prop the display stand up with a can of paint to keep it from falling over.”

Value Propositions:

- Effective planning

- Productivity

- Membership in a community

The individual narratives varied in length, from 500 to 1,500 words. This easily digestible format made each narrative easy to present at the beginning of a meeting, and equally consumable to people unfamiliar with the project and those intimately involved.

Narratives Have Power and Prowess

The power of user narratives lies in this accessibility and in their chameleonic nature. In the early planning stages at Kronos, we used the user narratives to provide a sense of scope so we could begin identifying workflow and information architecture that would address the user needs. Later, the narratives were an effective primer for bringing senior project sponsors up to speed about who and what the team was designing for, and for onboarding new people into the project.

The power of user narratives lies in their accessibility and chameleonic nature

Using the narratives brought a refreshing new way to express the big picture and the details together in an engaging story. We found people identified more quickly with the business purpose instead of weaving their own story out of the functional requirements.

A good narrative will transform itself to meet the needs of the team employing it. Developers may create a user narrative to visualize the system as it will be used by a specific group of people, revealing use cases and requirements that might have otherwise remained undiscovered until the application was built. By using a narrative as an introduction and a leave-behind piece, stakeholders—including architects, testers, and service design teams—are able to understand users and their needs, serving to promote a user-centric view even as the UX is just forming.

Because narratives strive to answer questions about who and what and where, when, and why things are done—staying away from how things are done—they leave room for design teams to interpret the narratives for their own process. The narrative that developers use to optimize efficiency could be used to pitch an idea to venture capitalists or stakeholders. That same narrative could be adopted by researchers to help with usability testing, and by the marketing department as the basis for a campaign.

A narrative can go as deep as it needs to, for as long as it needs to, which is invaluable during fast-paced development, using lean and agile methodologies. In these environments, requirements are often being defined simultaneously with interface design. Starting with a narrative means that a team can identify the requirements and get feedback before designing, putting the focus on the requirements and not on the design itself.

Presenting Your Narratives

The very nature of a narrative is compelling to audiences. Humans are more likely to retain facts when they are embedded in a story—the narrative allows us to make an emotional connection with the information, resulting in higher levels of understanding and investment in outcome.

Understanding this, and realizing that the narratives could have a powerful impact across departments, our team wanted to present them in a dynamic way. We introduced the narratives to the company as part of a project kickoff, initially focusing on securing funding and resources while also confirming direction.

Given the diverse level of audience members, we elected to use a Prezi animated slideshow to bring the story to life in a very fluid way, using the narrative as a script while presenting photos of people, places, and things that contextualize the narrative within a realistic setting. We presented specific screen concepts of UI designs, highlighting how narratives drive design by focusing screen design.

The Prezi presentation was compelling

Conclusion

Our user narratives were received positively throughout the company, and have become an integral and ever-evolving part of our design efforts. We plan on continuing to use the narratives as a central theme, serving to connect what can at times be an overwhelming number of functional details that are produced in a product development lifecycle. They provide a consistent storyline to ground planning discussions right up to launching and training, and rescue related conversations from edge cases and dark alleys. Put simply: We love our user narratives.

Image of hardware store employee courtesy Shutterstock