Save

When an abundance of stakeholders are involved in a product, user research is the only way to focus a whole team on the real needs and goals required for success.

It’s also the only way to get people out of the habit of thinking “Well, I want this, so everyone else must want it too”—a view that I find much more common in enterprises than in smaller organizations.

Large enterprises bring with them some unique challenges when conducting user research. The last thing you want is to get approval for research and then end up with unusable data. In this quick guide, I’ll explain a process I’ve found useful for running successful UX research in the enterprise.

1. Plan for Users Who Aren’t Buyers

First, users and buyers are not the same people—and their needs couldn’t be more different.

Company leaders who buy software care about things like control, configurability, compliance, and the number of features, among other things. In contrast, the people who use software every day only care about one thing: getting stuff done effectively and efficiently. If they can’t do that, a really ugly death spiral happens–as more people realize they can’t get anything done with the software, fewer people want to use it, until eventually no one uses it any more.

As I explained in the free guide Practical Enterprise User Research that I wrote with the collaborative design app UXPin, consequences like the death spiral are why it’s so important to do research with end users as well as buyers. While it’s tempting to focus just on buyers because that’s where the money comes from, there is a grave danger in not focusing on end users as well. Since they use the product every day, their satisfaction is an important driver for product renewals.

The way to access these end users is not through the buyers themselves. The way to get to end users is to seek out and form a relationship with the people and teams who are responsible for implementing the software once it’s bought. Offer to sit with them as they go through an install, or simply give them your email address if they have questions (and help them when they do have questions!) These are the people closest to the ground, and they usually care a great deal about the success of their users. I’ve never heard an IT manager (or similar) decline a request to spend time with some of their end users.

It doesn’t help if your company does an amazing sales job, but end users are so unhappy that the accounts don’t get renewed after the first year. Seek those end users out.

2. Write a Concise User Research Plan

I’ve given up on writing long research plans for stakeholders to approve. They just don’t read them (would you read them if you didn’t have to write them…?) Instead, I write a short one-page online document from a simple template with a few key sections:

- Background. This includes any background documentation about the project or the team, or sometimes just a single sentence to set the stage, such as “We’ll be doing 1:1 usability testing on the […] application the week of March 7th in the Palo Alto office.”

- Methodology and Schedule. This is a brief explanation of the methodology (what kind of research, how many users, the target market, the location) and a table with the schedule that fills up as users are scheduled. This gives stakeholders an opportunity to come back to the same place to see the progress of the planning.

- Goals (overall and specific). This sections is a brief overview of what the study will cover, and serves as a good outline for the research script for when the time comes to write that.

- Outcomes. Very importantly, this states what we will “get” from the research. For me, it usually includes 3 statements:

- A prioritized list of recommendations to improve the usability of the application.

- Product recommendations to increase the utility of the applications.

- Product Marketing recommendations to help overcome possible barriers to adoption.

This is a short document, but it allows everyone in the organization to comment on and eventually agree on the purpose of the research. This not only helps with script writing for interviews and usability tests–it also ensures that no surprising assumptions from stakeholders will surface later on when the research is all done.

You can actually get a user research report template (along with five other useful user research documents) in this free usability test kit.

3. Focus on Core User Research Methods

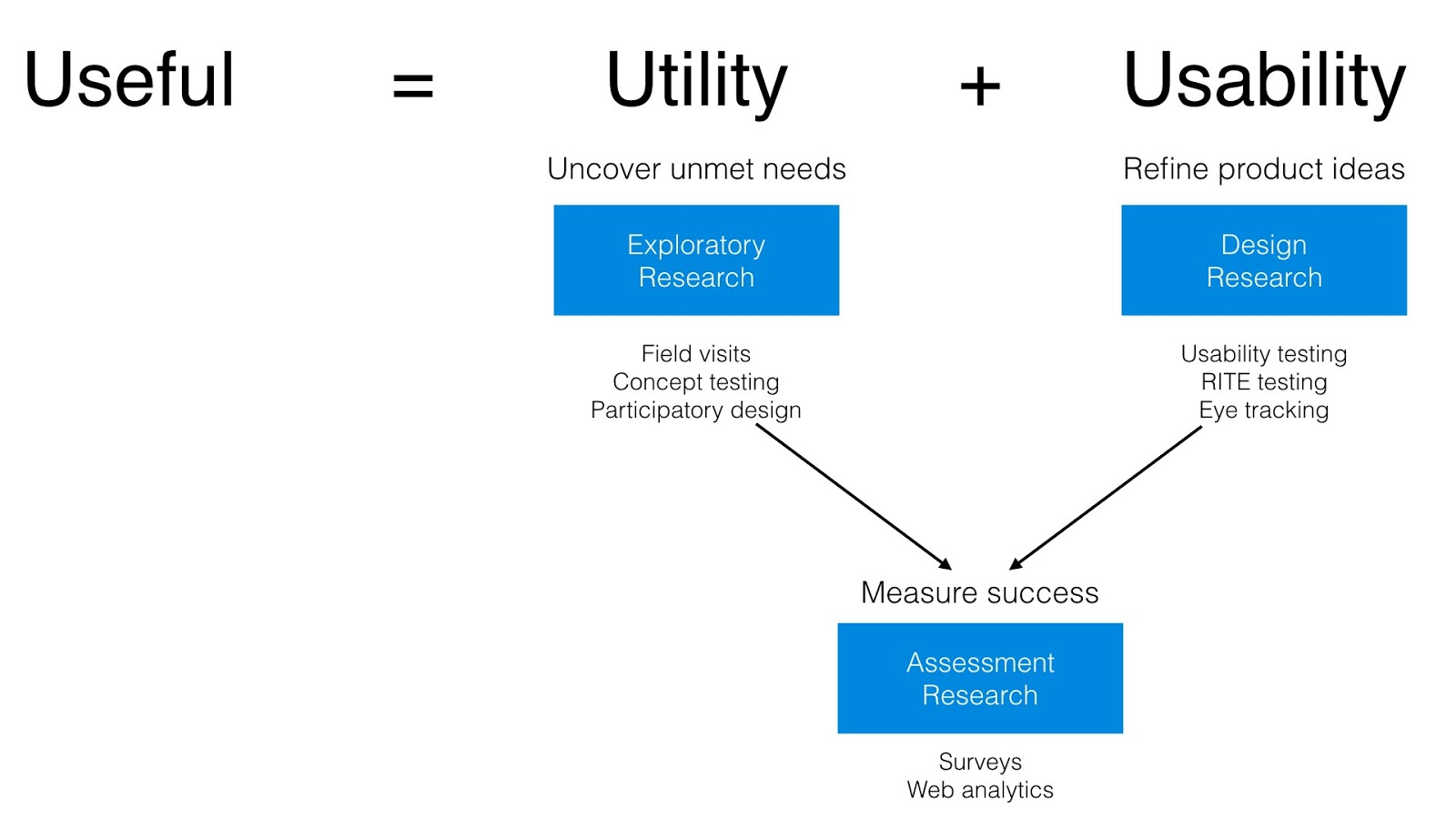

As is often the case, it’s useful not to throw All The Research Methods at a problem. Too many data sources can be as confusing as too few, and you also don’t want teams to feel overwhelmed by all the different ways you’re collecting data. Even though you can expand later on, my advice is to start enterprise research with two primary methods, both linked to the age-old Useful = Utility + Usability equation.

I usually employ the slide below to explain the difference between utility and usability, and what role research plays in understanding each of those concepts. In particular, I explain that utility research aims to uncover unmet needs, which is where all the best product ideas come from. The goal of usability research is then to refine product ideas until they’re the best they can be.

For this reason, I recommend the following research methods as low-friction starting points for enterprise UX research:

i. Ethnography to uncover unmet needs.

There is simply no better method to build empathy for user problems than interviewing users in person, in their natural context.

Whether that’s at work or in their homes, these interviews are hugely beneficial at the start of a project to understand the users you’re making the product for, and what they might need from the product. Practical Ethnography and Talking to Humans are great places to start learning about the basics of ethnography.

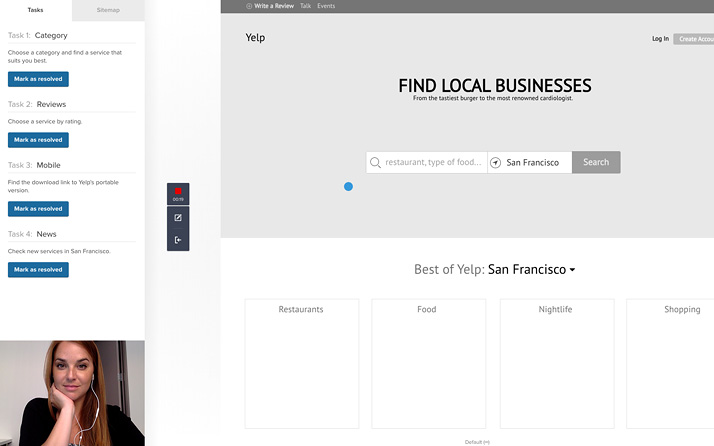

ii. Traditional usability testing to refine product ideas.

This is still the most solid method we have to systematically improve the user experience of an existing prototype or product.

As much as remote testing is becoming popular, I’m still a big fan of in-person, moderated usability testing. This allows for much more in-depth discussions and unexpectedly useful deviations from the script. It also enables researchers to ask some general interview questions to help shape the direction of the product.

For in-depth tips for ethnography and usability testing, you can check out the free 100-page Guide to Usability Testing.

4. Record and Document Your Sessions for Better Collaborative Analysis

It’s common for project teams to be very large (eight or more people) in enterprises. This can be a problem—even if everyone has bought into the idea of research—since you can’t take eight people with you on every study.

However, it’s important to keep everyone involved in the process throughout, which means you need a good plan for recording and viewing research sessions. Sometimes this means physical recording of screens and devices (I’ve written about this before in the technical guide to mobile usability testing), and sometimes it means taking really good notes.

I haven’t seen a lot of articles on how to take good research notes (especially when you’re on your own), so let’s dig into that a little bit.

The ideal situation for any qualitative research project is for the facilitator to rely on someone else to take notes. That way, the facilitator focuses all their attention on the participant. This holds true for contextual inquiries, in-depth interviews (IDIs), as well as usability tests. However, sometimes it’s just not possible to have a separate note-taker on a project. In those cases, the interviewer has to take their own notes—but that can be distracting and terribly inefficient.

Users and buyers are not the same people—and their needs couldn’t be more different

So, what’s the best way to be your own note-taker?

I’ve seen interviewers taking their own notes in a variety of ways, but the inherent flaws in each approach has always made me uncomfortable. Some interviewers use their laptops to make notes during the interview. This is very efficient (there’s no transcribing afterwards), but the clicking of the keyboard can be distracting and off-putting to the participant.

Others print out their interview scripts and leave blank spaces for writing notes about each question. The problem here is that scripts are fluid. You sometimes skip over questions, while other times you go off on an important tangent that isn’t covered in the script. So you tend to end up with empty spaces and cramped notes, all spanning multiple pages. Not ideal.

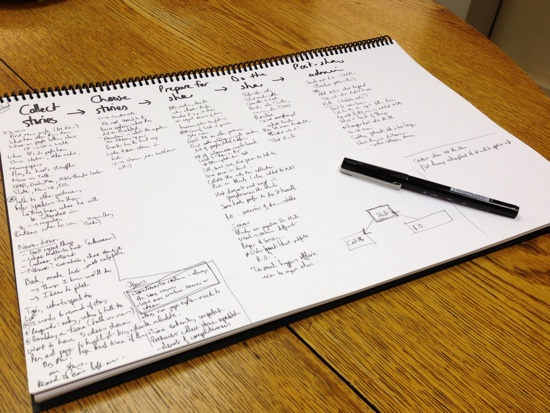

I recently worked on an enterprise project to make it easier for talk radio producers to do their jobs better. As a first phase, we did a bunch of in-depth interviews with producers—and I had to take my own notes. So I decided to try a new approach, and I now take all my notes this way.

I started the project with a long, free-form interview (lots of open-ended questions, but no formal script) with one of the project leads to develop a generic user journey for producers. I looked for common elements that remained constant regardless of the process each producer might use to perform their tasks, and used that to build a basic journey model for talk radio production. It’s not a full-on journey map, just a list of steps that all producers have to complete when they put on a show.

I then created an A3 sheet (6.5 x 11.7 in) for each interview, consisting of the participant’s name, time slot, and the headings for each of the steps in the journey. While conducting the interview, I filled out any insights that came out for each of the steps — as we worked our way through the script.

Here’s an example of what a sheet looked like after an interview:

I discovered that this approach has several advantages over other note-taking methods I’ve tried:

- It’s script-agnostic. The interview questions address each of the steps in the journey, but I don’t have to stick to it religiously—it’s okay to jump around and make notes in a different column if needed.

- Everything is on one page. This not only makes note-taking more efficient, but it also makes the analysis phase easier. I’m able to lay out the sheets on a table and see all the data in one place as I start the affinity diagram process.

- It makes me a better listener. I was worried that the note-taking would be distracting to participants, but I found the opposite to be true. By taking notes while we talk (and looking them in the eyes when I’m not writing), participants could tell that I’m really listening to them—not just pretending. This made for much better interviews.

- It’s a good artifact. By adding photos of the notes to a report (or passing the notes around) stakeholders can see the raw data in an easily consumable format, which increases their confidence in the findings.

I’m sure this method of note-taking isn’t perfect, but I’m quite happy with how it turned out, and I hope you find it useful too.

5. Always Show Your Work

I’ve found that how you effectively analyze and present results is different in enterprises than in smaller companies.

In smaller startup environments, the product team usually has very little need for “reports.” Researchers just work directly with product managers and their teams to make improvements. But in enterprises, it’s not that simple.

The most important tip I can offer is to show your work.

No matter how bought in the organization is on the need for research, a level of skepticism will remain—especially if they don’t like what the results are saying.

- Always begin reports with some background. Reiterate some of the reasons why research is important.

- Show photos of the participants, videos of their most poignant statements, and definitely show your affinity diagram process (before and after whiteboard shots work really well).

All of this fulfills a simple goal: to show you’re not just randomly pulling “actionable findings” from a black box. Once people see the methodology and science behind research, they’ll be much more receptive to the insights.

Conclusion

User research is an immensely valuable tool to improve an enterprise product’s user experience and business value. For some reason many enterprises have unfortunately lost sight of this fact, and research got a bad name.

My hope is that this quick guide will help my fellow frustrated UXers make some headway in practicing user research into the product development lifecycle.

Now it’s your turn to go forth and research. As you build momentum with each incremental result, your organization will become much more open to a thorough research-driven product development process.

If you found this article useful and would like more specific EUX research tactics, check out my free ebook Practical Enterprise User Research. I wrote it with the collaborative design platform UXPin based on my past 10 years designing in the enterprise.

Rian van der Merwe

This user does not have bio yet.