Save

Chayn is a survivor-led community, which means we practise trauma-informed design and prioritise trust and safety over aesthetic or simplicity. Often, this also means we have to go the long way to embrace the complexity that is commonly flattened in favour of post-it sized personas and cardboard empathy maps. Since 2013, many hundreds of hours of research, creating, testing, learning, unlearning and experimenting have gone into how Chayn’s design supports survivors of abuse — across different types of needs, languages, cultures and political landscapes.

In this series, I’ll be explaining the design principles that have come to feature in all of our work. It’s going to be a long post because it’s hard to capture the nuance each principle involves. Though I’m the one who has driven this work — and am the one recording it here — there have been a host of people involved in getting these ideas to where they are now. The feedback from survivors on our products, services and our words has shown us that design can be both transformational and transportive. Survivors have told us that they’ve felt understood after decades of self-blame that Chayn gives them hope in times of darkness; we told them that they were not alone. I always tell our team that when we design online tools — we need to approach it like we are designing a cafe. What do we want people to think about our space when they stand on the street looking at our cafe window? What would it feel like if they stepped inside? Would they want to take a seat and linger, or would they want to grab something they need quickly and go? Do they feel like they can do both depending on their mood and routine?

These principles may continue to evolve over time, so I’m sharing these now to show where my thinking is at present, and so our collaborative design may be further refined and better practiced across the globe.

Understanding trauma

Trauma is an emotional response to one or many terrible events that involves a risk of harm or danger to ourselves or others. The threat can be a threat to our life, such as assault; sense of self (as in emotional abuse); or our personal identities, like the everyday experiences of racism. Behaviours and norms that destroy, invalidate or erase our sense of identity, our wellbeing and sense of self can cause trauma.

A traumatic situation can evoke different reactions for different people. Trauma is never prescriptive. When internalised, trauma can make us feel frightened, humiliated, rejected, abandones, trapped, ashamed and powerless. It makes us feel unsafe in our bodies, minds and within our wider communities.

A trauma-informed approach thereby acknowledges:

(i) the prevalence of trauma;

(ii) how trauma affects all individuals involved with the programme, organisation, or system, including its own workforce;

(iii) and responds by putting this knowledge into practice.

(SAMHSA, 2012)

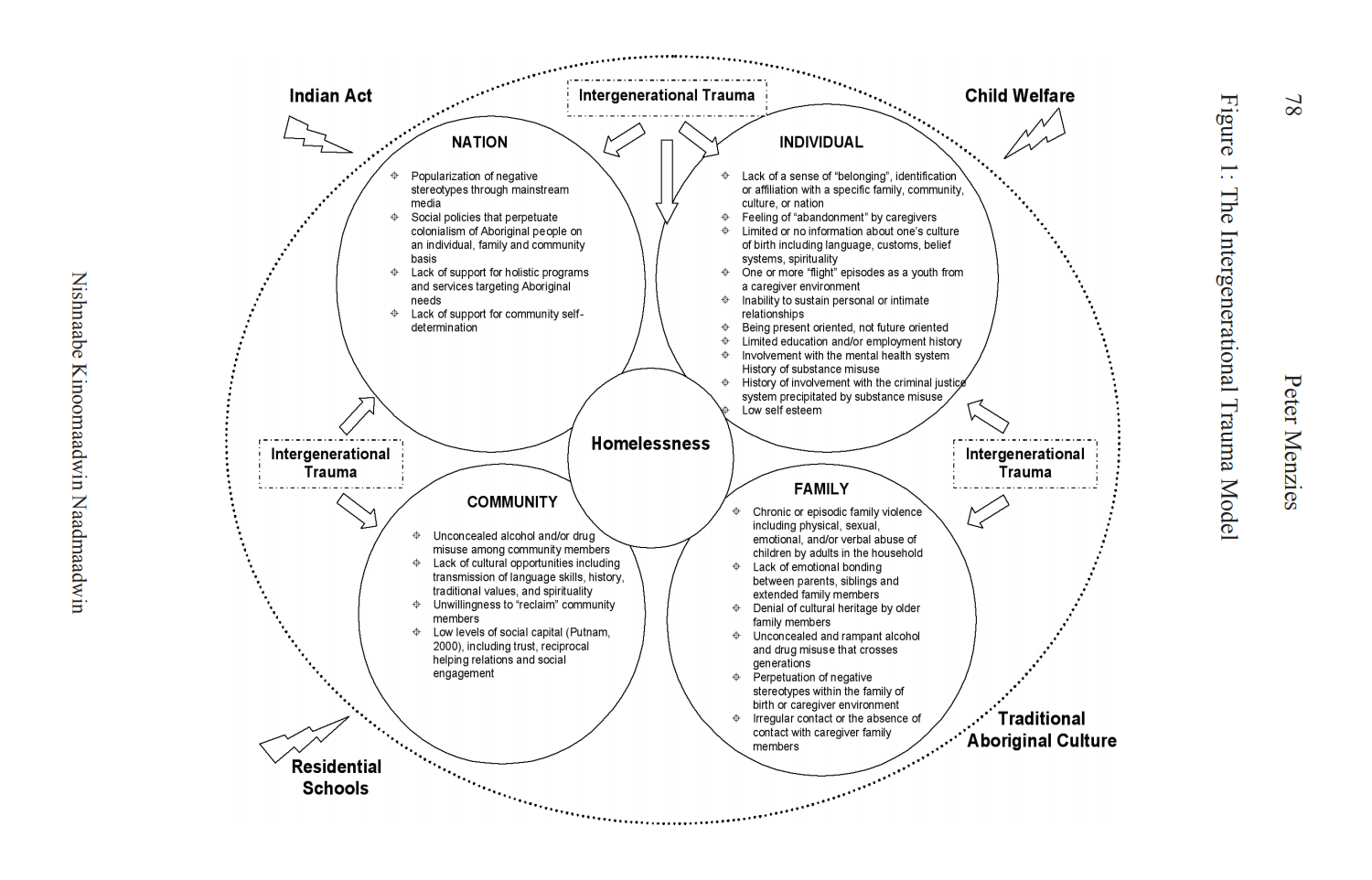

The impact of trauma can affect a whole group of people — and even extend beyond life. Intergenerational or transgenerational or ancestral trauma generally refers to the ways in which trauma experienced in one generation affects the health and well-being of descendants of future generations. It’s a new field we’re learning more about every day. Some studies show that children of Holocaust survivors can present with an epigenetic change in their system, likely connected to the Traumatic Stress of their predecessors. Similarly, the impact of oppression, residential schooling and the suppression of First Nation cultures in Canada has shown to make future generations of First Nations peoples more vulnerable to various social conditions and adverse experiences — such as substance abuse and family violence. This is a human condition and experience. As we grow up, we absorb the experiences, attitudes and beliefs of our family, relatives and community on a psychosocial level. This might manifest in working class people not being able to trust services run from wealthy parts of town where they have faced exclusion; or children of migrants prioritising financial safety over their mental health, because of the instability and monetary anxiety they grew up around; or children of addicted parents falling into addictive patterns themselves.

I’ve been reading a lot about intergenerational trauma and how it has resulted in lost generations of Indigenous people in North America. The work done by Indigenous psychiatrists and sociologists have helped me reflect on how I myself have been affected by some part of it, in the context of British colonialism and the India-Pakistan partition in 1947.

I saw this quote by Dr. Cornelia Wieman, M.D. FRCPC, Six Nations of Canada, the first Aboriginal psychiatrist of the country that really explains it so well: “I think you’re dealing with generations of people who have been damaged by colonialism, and the way that we have been treated by the dominant culture makes you feel dispirited. You feel devalued and so people will turn to things like addictions as a way of coping, of self-medicating, of not really wanting to be here because their situation is just so intolerable.”

These scars that communities inherit manifest in dangerous, confusing and damaging ways. For instance, in the United States Native Americans experience PTSD more than twice as often as the general population. The model below by Peter Menzies (Clinical Head of Aboriginal Services Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Toronto) does a great job of thinking about homelessness and its connection to intergenerational trauma.

This is an essential part of understanding the complexity that surrounds many of the user groups Chaynworks with — they’re likely the people you’re working with, too. And it is only in this understanding, connection and community that there can be healing. Our lives intersect — and it’s our job as designers, creator, and organisers to nurture these environments: for our digital lives and services to replicate the external mechanisms that we have all internalised.

Healing

Where there is trauma, there is room for healing — but the route to heal will look different for everyone. Especially if trauma is continued and chronic, meaning someone has been made to feel unsafe within themselves and in the world. Our foundations of control, entitlement, agency, love and care are affected or compromised by sustained abuse.

Something we’ve been thinking about at Chayn is that everyone tends to oversimplify what it means to “heal” to make it more convenient as a process. It is daunting to think that healing is messy, not linear and can take either a short or a very long time. There’s no universal map by which we can navigate.

However, in the way we think about healing, we want to embrace that unpredictability and the pain of it. From that pain and acceptance comes resilience. There might not be a “before”, a “normal” self without trauma, or an “after” — which implies ways suffering made someone stronger or better. Healing simply is. I’m not calling these restorative design techniques for an explicit purpose. Instead, restorative design is rooted in the principle that you can return a user to an original state, from potential distress. Yet, Chayn’s experience suggests that for some, especially those who have been cycles of abuse or been abused since childhood (whether in their familiar or close relationships or by larger systems of power), there is no before or after. It all just feels like a series of endless abuse.

In fact, this is a subject of a new research project — thanks to a grant from a generous funder. This part is so relevant to this section that I’m pasting an excerpt that I worked on with Alyson and others from Chayn.

“Whether in the linear course from hurt to improvement — or the cycle back to a standard — too often, rehabilitation is treated as something quantifiable, with people as products made shiny and new. But, a survivor’s journey post-trauma is never universal, and our treatment of trauma cannot be one-size-fits all. Healing abuse is not a business. It must be active, adaptable, interactive, communal, and questioning. We don’t need performative interventions — we need effective and soulful ones, which understand the nuance of complex emotions and realities. When a survivor’s self is damaged in the act of abuse, the self must become central to our restorative practices — lest we repeat the violence of abusers.”

An evolving set of trauma-informed design principles

A literature review of trauma-informed practices will reveal many values but mostly focus on ensuring user safety and preventing re-traumatisation. In a physical setting, this would mean thinking about the reception space of a clinic or else removing triggering sounds, objects and smells from a treatment area.

Using the principles of trauma-informed care — and combining it with Chayn’s eight-years — experience in creating content and services for survivors of abuse across the world — I’ve narrowed down a design framework which helps me test, rationalise and question our product decisions. These values have long lived in a Notes folder in my Macbook, which I bring out when we have team meetings. (For the sake of sharing our thinking and inviting you to share yours,I’m penning a work in progress.)

We must not generalise or flatten user experiences into needs that neatly fit into one post-it. People live in a multi-dimensional world and therefore, our understanding of their needs, journey, challenges, fears, hopes and aspirations must hold space for that complexity and richness of nuance.

The following design principles were a lot less a few years ago and I expect these to change in the future too as I learn, practise and share more:

- Safety: We must make brave and bold choices that prioritise the physical and emotional safety of users. This becomes critical when designing for an audience that has been denied this safety at many points in their lives. Whether it is the interface of our platform or the service blueprint, safety by design should always be the starting point.

- Trustworthy: Build trust with transparent, clear and consistent communication and design. People who experience trauma have often lived through internal and external unpredictability. Good, intentional user interface builds credibility in the first interactions — but it’s the service itself that will do the rest. One way to build trust is to be consistent and predictable.

- Plurality: To do justice to the complexity in human experiences, we need to suspend assumptions about what a user might want or need and thus account for selection and confirmation bias. A refugee might not be able to speak English but may be able to competently converse in “texting” English.

- Agency: Abuse, inequalities and oppression strip people of agency. We must always make sure we do not use tactics of oppression to ensure we can redistribute power and agency by providing information, community and/or material support.Users and survivors of abuse should be a critical component to their own path to wellbeing, not silenced.

- Open and accountable: For Chayn, this also means practising the values of openness and collaboration with our partners, banishing the spectacle of perfection performance and embracing the risk of failure that comes with holding uncertainty as dear as knowledge.

- Solidarity: There is no single-issue human, therefore all of our interventions need to be designed with that in mind. Even if our services focus on one aspect, we need to signpost to other needs to provide the best relief.

- Empathy: Abuse can leave us feeling like no one cares about us and, at times, that we don’t even care about ourselves. Empathetic, warm, soothing and minimally-designed interfaces and narrative should feel like a virtual hug, motivating people to both ask for and embrace the help we can offer. It should validate their experience as we seek out collaborative solutions.

- Friction and privacy: We should remove unnecessary obstacles from users getting to the information and help they require, although some friction is necessary to protect user data and personal rights.

- Hope: People who come to our services are often in positions of pain or of trauma. They do not need to be reminded of their own struggles, experiences or difficulties with harsh words and sad pictures — many of which are facsimiles of an abusive experience, organised in sensationalism rather than truth, or are shocking for the benefit of an audience rather than the survivor themselves. It’s scary and brave to reach out for help:our virtual spaces need to feel like an oasis for users, not another place of stress, Othering or misunderstanding.

Hera Hussain

Hera is the Founder and CEO of CHAYN - a global survivor-led project creating open resources on the web to address gender-based violence.

- Trauma-informed approach to design allows to consider how traumatic experiences affect users and find inclusive solutions that will meet their needs.

- By following specific principles, it is possible to unlock the transformative power that design might have for human beings.

- Above all it is necessary to prioritize user safety and prevent re-traumatization by conducting an in-depth research of users’ fears and needs.