Too often the needs of those from marginalised groups are excluded from the design of the technological touchpoints that serve society. This has resulted in further social exclusion of people from these groups.

Inclusive design has been promoted as a way to change the exclusion of these groups, however, there are currently barriers to adopting this approach. Firstly, the term “inclusive design” is ambiguous as there is no single clear definition. Some definitions are in contrast with one another and some even exhibit exclusionary undertones. Secondly, when it comes to practising inclusive design for technology, traditional User-Centred Design (UCD)approaches fall short.

This is the first of a two-part series of articles where I aim to remove ambiguity of the term “inclusive design” and provide insight into the mindsets, approaches and processes that designers can adopt to improve the inclusivity of future technology products and services.

This article (part 1) is organised into two sections. In the first section, existing definitions of inclusive design are examined to create a clear unified interpretation that exhibits an ethical position. In the second section, the traditional UCD approach and mindset are evaluated to provide insight into why designers need to shift to a participatory mindset to successfully create inclusive technology products and services.

In the second article (part 2), I will explore participatory and co-design methodologies and approaches that can be effectively used in designing inclusive technology products and services.

What is inclusive design?

Before adopting inclusive design it is important for designers to understand the principles associated with that approach. However, this is no easy task as several definitions exist with differing principles. A definition of inclusive design provided by the British Standards Institute states:

Inclusive design is the design of mainstream products and/or services that are accessible to, and usable by, as many people as reasonably possible on a global basis, in a wide variety of situations and to the greatest extent possible without the need for special adaptation or specialized design.

The definition from the British Standards Institute mentions the phrase “reasonably possible”. This infers that the decision of who can participate in the use of products/services is dictated by the practitioner of inclusive design. People other than those deemed “reasonably possible” could be excluded. According to Åhman et al, if decision-makers deem the design of products/services too difficult or costly then there is the possibility the inclusion of people with disabilities can be disregarded. With this perspective, the definition of inclusive design from the British Standards Institute alludes to an approach that could result in exclusionary products/services for some marginalised groups.

The marginalised population is large and diverse. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2019), approximately 18% of the population has some form of disability. In addition to those with disabilities, marginalised people can be grouped according to shared common features or outcomes (e.g. reduced access to health or financial services) or because they have other differing attributes (e.g. sexual orientation, gender, geography, ethnicity, religion, displacement and conflict). These large populations must have equal access to technology products and services. Inclusive design must focus on the needs of marginalised groups and these needs should be placed at the centre of the design process.

According to Newell et al. “inclusive design is a way of including the needs of marginalised user groups within the design process.” This statement suggests the needs of people from these groups must be considered throughout the entire design process, they are not optional. Following this principle, inclusive design practitioners acknowledge those from marginalised groups must have absolute and unconditional rights to participate in all products/services they design.

Another definition of inclusive design is provided by Susan Goltsman, a leader in the field. Goltsman states that “inclusive design doesn’t mean you’re designing one thing for all people. You’re designing a diversity of ways to participate so that everyone has a sense of belonging.” In this definition, Goltsman champions an ethical perspective that acknowledges the varying abilities of those that require inclusion.

The definitions provided by Newell et al. and Goltsman offer complementary values that when combined create an ethical, holistic vision of inclusive design. Building on these perspectives I have developed the following definition:

“Inclusive design can be defined as an approach where the needs of marginalised groups are always considered and included throughout the entire design process and although the product/service isn’t required to be one thing designed for all, it should be flexible and consider a variety of ways people can participate whilst feeling a sense of belonging.”

Throughout this article, when mentioning inclusive design, it will be this definition inspired by values from Newell et al. and Goltsman.

A shift in mindset

Because inclusive design requires the needs of marginalised people to be addressed throughout the design process, designers must work closely with those who will be impacted by the outcome. The inclusion of their needs dictates what product/service is most appropriate, helping to ensure the future success of the outcome. This becomes even more important with Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) projects as technology continues to touch every aspect of society.

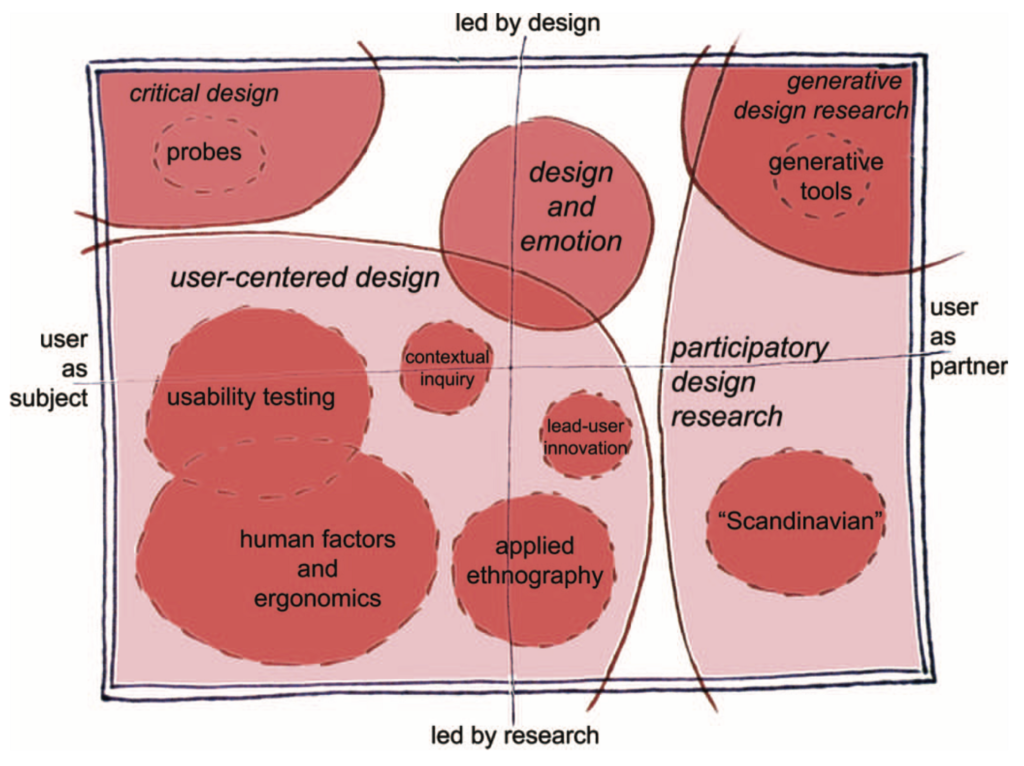

Traditionally, technology products/services have accommodated the needs of people following a UCD approach. The UCD approach was established to ensure users’ needs were placed at the centre of the design process. Although UCD places the user at the heart of the process, it is not best suited for inclusive design projects. UCD focuses on the end product or service fulfilling the needs of people, however, this approach risks the needs of marginalised groups becoming an afterthought or an add on. UCD doesn’t consider the dynamic nature of people’s abilities resulting in static interfaces and systems that consequently ignore the diversity of ways people require participation. According to Sanders and Stappers, UCD describes a culture characterised by an “Expert Mindset”, where designers are considered as experts and users are seen as subjects that inform the design process and outcomes. Figure 1 shows how UCD activities fall within the “User as Subject”, “Led by Research” quadrant.

The expert mindset can be seen in UCD activities such as usability testing and user interviews (contextual inquiry). In these activities, the designer develops research goals that are informed by their assumptions, experiences and desired outcomes for the business. From the research, insights into the user’s needs and pain points are uncovered, however, the designer still has agency over which needs and pain points are prioritised to solve for and what the solution will be. The designer has control over the product/service outcome.

For the reasons mentioned, it can be argued that UCD isn’t appropriate for the successful design of future inclusive HCI products/services. For inclusive design to succeed, a shift from an expert mindset to a participatory mindset is required. A participatory mindset is characterised by actively involving the people who will be impacted by the outcome in the design process. These people are seen as partners or co-creators. Treating a community as co-creators, empowers them to decide the course of action and ensures the product/service meets their needs. This approach is particularly important when the course of action will impact those in marginalised groups who have been socially excluded. By adopting a participatory mindset, designers shift the focus away from their own experience and expertise and instead focus on the needs of those from marginalised groups.

One of the core principles of the participatory mindset is the democratisation of the design process. With the democratisation of the design process, control of the product/service outcome, traditionally held by the designer, is shared with the people served by the outcome. For marginalised communities, this humanising process creates a partnership between them and the designer. Designers with this mindset understand the privileged position of power they hold. They’re aware of the decisions and actions they make determine who can and can’t participate in the touchpoints of society. With the democratisation of the design process, designers take a step closer to uplifting those in marginalised groups.

A participatory mindset does not consider completely removing power from designers. Instead, it promotes sharing the experience of design with those affected by the outcome and empowering them to decide their future. According to Bratteteig & Wagner “community empowerment starts when people listen to each other, engage in a dialogue, identify their commonalities, and develop solutions for their own problems.”

The participatory mindset also reflects the principle that all people have the capacity to think creatively. The creative capacity of all was first recognised by influential twentieth-century social scientist Herbert Simon. According to Simon “everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations, into preferred ones.” This principle can help designers overcome their assumptions by “seeing design as a capacity and mindset that everyone has, and has the potential of doing well.” For products/services to be inclusive, designers need to enable people the opportunity to create outcomes that will best suit them.

The participatory mindset not only democratises the design process and acknowledges everyone’s creative potential, it also ensures technologies are not built based on assumptions influenced by people’s biases (Holmes, 2018). When considering inclusive design and marginalised groups it is especially important for the designer to recognise ability biases. This is when the designer uses their own abilities as a baseline to inform decisions (Holmes, 2018). By including people from marginalised groups in the design process designers are better equipped to overcome these biases.

I acknowledge shifting to a participatory mindset is a challenge as the principles can be difficult to embrace. This might be especially true for traditional UCD practitioners. However, it is possible for designers working on inclusive products/services to shift their mindset. They must develop an understanding that people with lived experiences can and should influence the outcomes that affect them. Holmes states (2018) “people who’ve experienced great degrees of exclusion can translate that expertise to the solutions they create” (p.64). Additionally, if communities are empowered to highlight the concerns that are critical in answering what will potentially influence their futures better outcomes can be achieved. Over time and with continual development, designers can build the skills and knowledge required to transition to a participatory mindset.

Holmes, K. (2018). Mismatch : how inclusion shapes design. The MIT Press.

Simon, H. A. (1969). The sciences of the artificial. M.I.T. Press.