Save

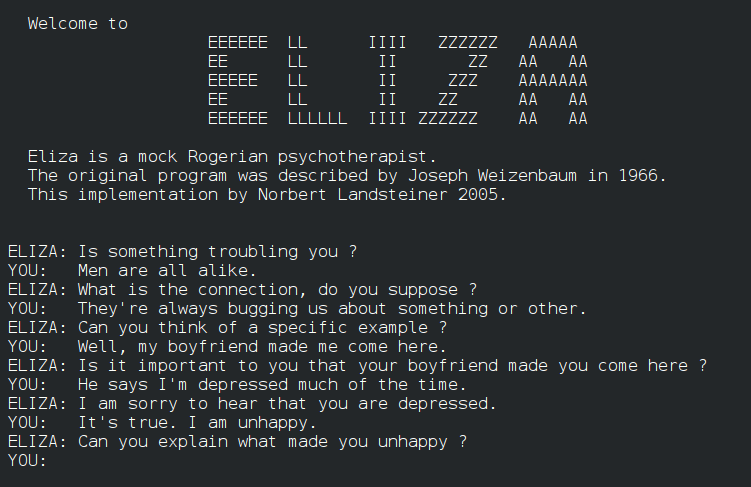

Joseph Weizenbaum, a computer scientist at MIT created the first natural language computer program called ELIZA in 1964, a precursor to the chatbot we put up with today. It was text based interaction, and a person would type in their question to the terminal where ELIZA would come back with another question on screen. The programme didn’t need to know anything about the person it was interacting with to elicit genuine information, it simply reflected questions back to them, with many happily divulging personal information. It never delved deeper, but showed an effective way of asking questions.

Forty years later, Alastair Somerville, a sensory design consultant, gets strangers to sit across from one another and tell each other a story of their life. The other person then recounts the story as best they can. In his workshop called Architecting Emotions, he illustrates how difficult it is to listen and ask effective questions.

I am one of these strangers and find it excruciatingly difficult to recount most of what the other person told me, and this is not just a problem with my crappy recall, it’s universal.

Stop asking about feelings

Sitting across from another stranger, I am told to interject and ask questions when I think I can detect an emotion, either sadness, anger or happiness, from my interviewee. I think I have been attentive, but Alastair, like a genial uncle, points out I had inputted my own feelings and experiences into the questioning and uncovered no meaningful insights.

Not only is it hard to listen for the salient emotions, it’s also difficult to draw them out without affecting them. We tear what we touch.

UX designers and product people have a fear of masterly inactivity

We pose questions to users of our products and services such as ‘How do you feel about this, was it bad?’ and ‘Sorry to stop you there, did you like it or not like it?’. UX designers and product people have a fear of masterly inactivity. Surely it’s our job to ask probing questions, extract information from our users effectively and quickly? We talk at every turn, trying to coax a satisfying answer from our users. Being so direct feels like the correct thing to do, but does nothing to give voice to the person’s genuine feelings.

Creating a state of ‘empathy’ is especially difficult under pressure. There’s that ‘empathy’ word again, a word that Irene Inouye says ‘… is not a birthright bestowed upon the emergent designer. Rather, it is a skill like any other skill such as surfing, driving a car, or meditating.’

Recounting emotional and stressful events blocks one’s cognitive abilities, making us unable to pinpoint and analyse our emotions. An emotion like anger or shame cloud our thoughts, constricts our cognition, making us unable to say what we mean, therefore it’s difficult to gain authentic insights from people we question.

Step out of the frame

A better way of communicating is to ask a question and then step out of the frame. The person may not know the answer, so we reflect the question back, holding up a mirror so they can work it out for themselves, instead of trying to answer it for them.

Influential therapist Carl Rogers and a founder of the person-centered approach to psychology believed ‘it is the client who knows what hurts, what directions to go, what problems are crucial, what experiences have been deeply buried.’

Inspired by Rogers, Weizenbaum created his most famous script for ELIZA called DOCTOR, which mimicked a Rogerian psychotherapist, and employing the person-centered approach. If the patient said that ‘I am unhappy’, this Rogerian psychotherapist would ask ‘Why do you feel unhappy?’ and so on, giving the patient all the time to discover new insights for themselves.

Alastair summed up his workshop saying ‘when people are given limited ways of communication, they only have limited tools to express themselves’. True empathy is about stepping into someone’s space, which demands trust, respect and then having the skill to step out of the frame.

Steps for effective listening

- Avoid interrupting and give the person space to talk.

- Give the person time to reflect on the questions you ask.

- Avoid using your personal experiences to appear empathetic.

- Try to extract an emotion and give them space and time to name the emotion for themselves.

References

Acuity Design, Sensory design consultancy

Carl Rogers, On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy

Irene Inouye, The assumption of empathy

Joseph Weizenbaum, Eliza demo

François Mai, Masterly inactivity: a forgotten precept

Susanne Vogel & Lars Schwabe, Learning and memory under stress: implications for the classroom

David Hall

David is a seasoned designer who focuses on user experience, creativity and theories behind what makes art and design tick. He is Head of Design for C&R and helps create really useful SaaS solutions for some of the world’s biggest multinationals.

- One of the major challenges for UX designers is questioning effectively and letting users express themselves naturally.

- One reason for this challenge is low responsiveness, which leads to exploring new ways to get a satisfying answer from users.

- Recounting emotional and stressful events blocks cognitive abilities, making us unable to pinpoint and analyze our emotions easily.

- This article recommends giving users the time to figure out the answer for themselves without trying to influence their emotions.

Read the full article to learn how to listen effectively.