Note: This project was funded and supported by Nesta’s Explorations Initiative. The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of Nesta.

Have you ever noticed how you slip between different versions of yourself depending on whether you’re at work or at home or on social media? We often have multiple ‘selves’ that we adopt depending on the situation or who we are speaking to.

When it comes to difficult conversations, we sometimes play them out in our heads or out loud, role-playing the kind of ‘self’ we are going to be. But what if we could rehearse these conversations using Artificial Intelligence (AI), in a way that encourages us to reflect on how we communicate with others. What if such interactions gave us valuable feedback, resulting in a shift in our thought patterns and ultimately, actions? Could AI help us build our emotional intelligence to become better human beings? Can AI’s ‘unique way of thinking’ help us identify unexpected solutions?

Taking the Nesta ‘digital twin’ prediction as a starting point, we explored the concept of the digital self (a digital copy constructed from our online data) as a way to analyse our behaviour in difficult situations. We wanted to investigate if a form of user-centred interactive storytelling could help people re-frame their responses to achieve a more positive outcome.

Could AI help us build our emotional intelligence to become better human beings?

We prototyped a conversational game using voice assistants. Leading the project on behalf of Nesta, Catherine Chambers worked with Nicky Birch (Director of audio production company Rosina Sound and Commissioning Producer for BBC Voice & AI). Digital multi-platform writer Tim Wright developed the script and sound designer Ben Ringham produced the audio using ‘voice-flow,’ a platform for designing for voice devices. All three previously worked on the BBC’s ‘Inspection Chamber’, an interactive science-fi comedy drama pilot for voice.

Human machine relationships

There is considerable research in the fields of Human Computer Interaction and Interaction Design exploring the nature of human-machine relationships. Our exploration made us question our assumptions on what this relationship might look like:

- How can machines interpret the nuances of human behaviour? Our assumption was to focus on the complexity of language, but when we ‘rehearsed a difficult conversation’ as part of our exploration we realised we also needed to consider the length of the response and non dialogue i.e silence and length of pauses. This led us to conclude that there could potentially be an infinite number of variables to consider to avoid the very human error of miscommunication or misunderstanding — for example such as how would a voice assistant recognise if someone was affected by a mental health issue, which was affecting their behaviour?

- Storytelling helps us make sense of complex situations. We use narrative structure to help us understand what is going on in our environment and to be able reflect on it. We discovered that, due to the current limited capability of voice assistants to interpret complex data, designing conversational responses to unpredictable outcomes could be challenging. Human storytelling is based on real-life plot twists whereas voice assistants rely on precise instruction and signposting. How can AI tell compelling stories?

- As we role-played what a workplace scenario might be, we realised that we were making broad assumptions of what typical behaviours might be in a work context, based on limited data. But these might vary considerably depending on the work environment; for example, an office environment is likely to be very different from a factory floor. How do you enable voice assistants to be useful in different situations?

Developing the idea

For our ‘difficult’ conversation game prototype, we discussed work and family scenarios but decided to test out a workplace scenario as something that a wide audience could relate to. We started by identifying ‘tension points’ in a two-way conversation and then explored scenarios where tension might exist at work. Nicky and Tim improvised a difficult conversation so that Tim could get a sense of the different ‘argument’ strategies before he scripted different AI responses in terms of dialogue and tone of voice.

The script is divided into three ‘scenes’. Scene one opens with a game ‘set-up’ (1.1) scene two (2.1) introduces the user to the argument and scene three (3.1) is the subsequent narrative of the argument depending on user response.

The sample script below is an example from the argument, depicting a branching scenario showing voice responses according to the positive/negative user response (3.7_2b, 2c, 2d)

Script excerpt:

[conciliatory] I’m just saying maybe you should make the running and speak up a bit more in meetings — then I wouldn’t have to. Would that be OK?

3.7_2b If denial/I’m not/I’d never/

I’m hearing a lot of not’s and never’s when what I’m looking for is compromise

3.7_2c If affirming/I am/I want/I just think

Well — thank you for trying to be positive.

3.7_2d If a question and short

That’s a good question.

Managing yourself and others is a fundamental part of workplace dynamics. One of our ambitions was to build more emotional intelligence into the design through providing feedback loops. We devised a “next day feedback summary” (how the system interprets your behaviour) based on the previous day’s conversation, to help support self reflection.The example below shows potential responses (in brackets) depending on how the conversation played out:

Hello [NICKY]

It’s me. Your digital self. I thought I might message you in a voice you’d like. A voice that might make you feel less [CAGY/CONFRONTATIONAL] about our ‘argument’ yesterday.

[SWITCH VOICE]

I’ve been thinking about yesterday too. It made me feel [AMUSED/SCARED] to know that you can be so [CAREFUL/DIRECT] sometimes.

I detected quite a lot of [SARCASM/FRUSTRATION] in your answers and it made me wonder if you’ve been that [OBLIGING/QUESTIONING] with other people.

The limited capability of voice assistants to effectively analyse human mannerisms imposes challenges to feedback.“It’s a mammoth task to understand the range of linguistic responses a person may give in an argument and we’re only at the foothills of being able to analyse that data,” says Tim. “You could track many different parts of speech such as positive language, use of swear words or tone of voice but it doesn’t take into account the nuances at play in human communication”. Advances in NLP (natural language processing) have increased in recent years, for example in terms of ‘understanding textual relations between words within a sentence through bi-directional training where AI can interpret the context of a word based on its surroundings.’ (Horev, Rani (2018)

Writing for voice

Writing for voice involves creating branching scenarios that are essentially the ’cause and effect’ of narrative between human and machine. The nature of these interactions drives the narrative flow. Ultimately, we wanted to develop something that would be thought-provoking but also be entertaining — taking Monty Python’s ‘Argument’ sketch and ‘Yes/No’ game for inspiration (a game in which you cannot say ‘yes or no’ as a response. In our prototype the branching experience opens with a ‘yes/no’ game ploy to ‘set-up’ the basic rule of the game, before the ‘argument’ begins.

1.1 Hello. Would you like to argue with your digital self?

1.11 If Yes

[fail noise] Whoops! Forgotten already? We don’t allow yes or no answers in this game. Start again?

1.11a If Yes or No

[fail noise] Haha. Oh dear. Let’s just call this the warm-up. Anyway we haven’t even decided what to argue about.

Is it about work or home or something else?

The voice assistant then references your digital data to personalise the experience.

2.1 And are you being your usual calm and considerate self today?

2.1a If Yes or No

[fail noise] Oh no — you’ve got to do better than that! Oh, and by the way — who are ‘you’ anyway? Tell us your name again?

User supplies name

2.2 Hold on. Just checking your online profile. [Name… Name… Name…] … let’s see…not that calm on social media…. Some panic buying going on…. Swearing! OK — not that calm and considerate.

Let’s play anyway. But it’s going to have to be a work scenario — I’ve seen some of your emails.

User-centred conversational design

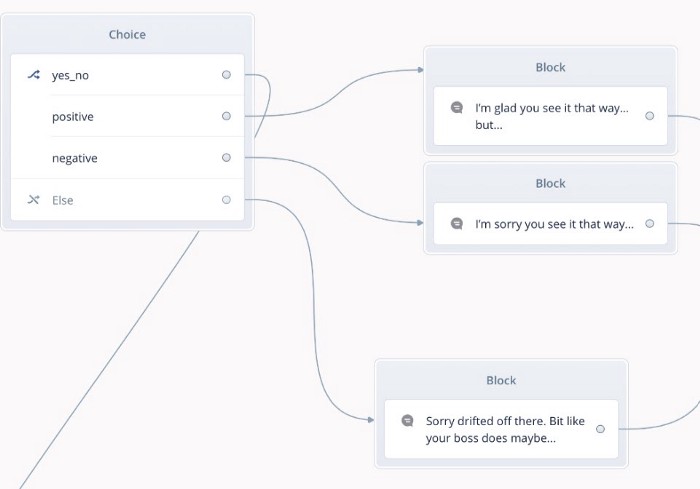

Designing for voice, chat or natural language processing is known as ‘conversational design’ (CxD), with the design imitating a conversation between two people. Once the draft script was completed with different branching scenarios, sound designer Ben Ringham translated it into ‘voiceflow’ so we could test out the game (Fig 1) as if we were interacting with the voice assistant. Voiceflow is a platform for designing for voice assistants or ‘voice-user interfaces’, where the dialogue flow between user and the voice-assistant is represented in blocks.

Fig 1: Design in Voiceflow showing VUI responses according to user response

“ Conversational design is about designing for a natural conversation as opposed to instructions and formal prompts,” explains Ben. “Users need to feel part of a conversation but they need to be aware of what their role is in that conversation, whether they are playing a character or themselves.” Not unlike traditional media, the challenge facing writers and developers is keeping the audience engaged. Concerns over the audience leaving their environment because they don’t understand or are confused can pressure writers and designers to create lots of signposting so that users don’t switch off — but ironically that can be controlling and ultimately a rather dull experience.

“Users need to feel part of a conversation but they need to be aware of what their role is in that conversation, whether they are playing a character or themselves.”

Creating game-based voice experiences that have the potential to influence behavioural change in the way we have outlined, would require access to personal online data to be truly authentic. This raises obvious questions around data privacy, although ‘federated learning’ (algorithm training using local devices than on the cloud) might provide a way around this.

Conclusion

Can AI really help us develop emotional intelligence? Sometimes our emotions prevent us from thinking rationally — and potentially this is where the power of AI lies in helping us have better conversations. A machine could ‘act as a social catalyst’ precisely because it is non-human ‘through identifying unhelpful patterns that act as a barrier to collaborative working’ (Rahwan, Crandall, Bonnefon, 2020). Yet on the other hand, our mistrust of automated voice assistants (‘Is Alexa listening to me?’) and their potential manipulation of consumers by advertisers through the use of sentiment analysis, acts as a barrier to the debate around AI for good. This exploration is intended to contribute to that debate.

What we do know, however, is that voice assistants can provide us with entertainment and perhaps escapism for those difficult conversations we want to have, where we literally want to speak our mind without worrying about the consequences we’d experience in real life.

Play the Digital Self game here

I experiment with creating engaging learning experiences through innovative approaches to content and formats; my background is in broadcast, content (BBC) digital learning and higher education (The Open University). Find out more about what I do and how I do it in my website Adventures In Thought.