While there remain certain specific contexts where it is advisable to craft and present wireframe layouts for client evaluation and approval, this practice is often a really bad move and one made at the wrong moment in the design process, and for the wrong reasons. Wireframes can be useful, valuable artifacts for informing the designer’s process. But they often fail miserably as a first-step deliverable for clients.

While there remain certain specific contexts where it is advisable to craft and present wireframe layouts for client evaluation and approval, this practice is often a really bad move and one made at the wrong moment in the design process, and for the wrong reasons. Wireframes can be useful, valuable artifacts for informing the designer’s process. But they often fail miserably as a first-step deliverable for clients.

The practice of compulsory client presentation of wireframes for all projects is not uncommon in the Web design profession. But rather than being based on sound, contextual reasoning, it is more often a thoughtless, vestigial process remnant or the result of careless misinterpretation of someone else’s contextually-specific best practice. Put another way, many designers generate and present wireframes to clients not because they know it’s a good idea in a specific case, but because they’ve seen or heard of others doing so and they therefore think they’re supposed to as well. As always these sorts of assumptions are problematic. An action or choice without context is a step toward failure.

In this article I’ll examine design and project management issues that surround wireframes, and how some specific contexts impact choices for producing and/or presenting wireframes to clients as project deliverables.

To wireframe or not to wireframe

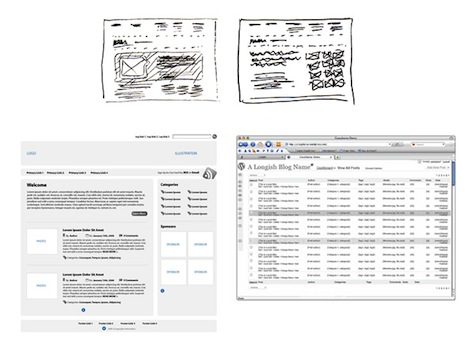

Whether they’re hastily-scribbled pencil sketches on notebook paper, detailed ink drawings on graph paper, rudimentary gray box layouts made in a graphics tool, or highly detailed monochrome comps with real text content and accurately rendered interface and form elements, virtually every project involves wireframes of some sort. They provide guidance for the rest of the design process …for the designer. They can, however, be problematic or useless for the client and in some cases they’re simply a waste of time.

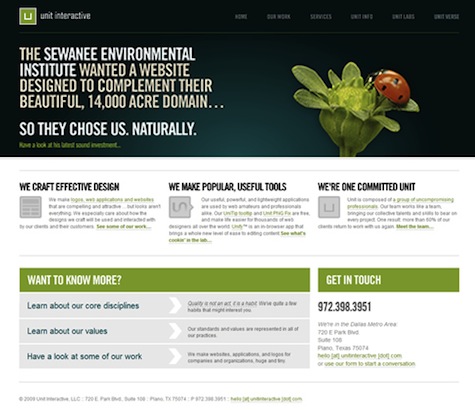

The value of this nice design (above) would not likely be well served by a wireframe presented to the client.

But not always. As mentioned before, there are certain contexts and cases where crafting wireframes for client evaluation and approval is a good idea or an advisable requirement. For instance:

- forms

- (some) Web app layouts

- news sites

- or in those lamentable situations where you’re asked to design without the client having provided you with the content (where wireframes are used to help them visualize how content volumes impact the layout. A poor process!)

These are good contexts for client-presented wireframes. All but the last example are likely well-suited to client wireframe approval because of what generally allows these types of pages to be successfully designed: the lack of visual noise and obtrusive, non-content graphic elements. For those contexts, the plain, monochrome wireframe presents a fairly clear indication of an ultimate result. In these cases, most of what can be conveyed by a wireframe can remain unaffected by the full articulation of the design (though “Web app” is an admittedly generalized example here).

Even in these contexts, however, the design process can get derailed by the client’s feedback and requests when made without the context provided by an already understood and approved full design direction. Wireframes are a sometimes useful “guess” that can help get design underway. But if your client doesn’t share your appreciation for and understanding of the purpose of wireframes, things can go awry. Sometimes it is best that the fully realized design for one or more promotional/information pages be agreed upon before wireframes for some other specific layouts are generated so that the comparatively inarticulate wireframes can be viewed and evaluated in the right context.

Some problems with wireframes

Wireframes bring with them a host of potential communicative problems that must be understood by both the designer and the client where wireframes are used. Taking into account that part of your job as the designer is to win and maintain your clients’ trust, you don’t want to introduce artifacts or documents that might work to erode that trust. Design-communicative problems erode trust.

Wireframes as the design blueprint

Some may regard wireframes as entirely innocuous; as merely the blueprints for the page layouts. This analogy does not hold. The blueprints or the floor plan for a house are made in the context of the fully realized design and the client views these with the benefit of having seen detailed elevation drawings or paintings. When the project is fully realized as the house is built, the blueprints and floor plan encounter no modifying influence or pressure to change. They’re set, solid. Their plan will likely hold through the entire process.

The floor plan above has the context of a design result as rendered in the elevation painting. Thus the client can form opinions based on a full, clear picture.

Wireframes, however, cannot easily accommodate and convey vitally important components of the design. Gray boxes and non-contextual dummy content cannot describe:

- how contrast impacts content hierarchy

- the impact of brand-specific design features

- the impact of graphic and textural elements

- the eye/energy paths created or interrupted by color and contrast of graphic elements

- et cetera

As a result, what seems logical and sound in a wireframe may be trite and malformed when the actual design and content are applied. Gray boxes and generic filler copy may fit together very nicely for an initial plan, but relationships can often change as the graphic and textural layers and actual content are added. Revision becomes likely.

The impact of informational and promotional content

The further the page purpose moves away from sanitary news or purely functional requirements the less effective and articulate wirefames become. Counter to the previously cited example, there are common cases where what will be a compelling, effective design fully realized may seem dull and dubious as described by an inarticulate wireframe. As such, it may work to erode client confidence.

For example, this wireframe (above) is not very exciting and in no way conveys the impact and effectiveness of the fully-articulated design that will follow. A client presented with this wireframe as an example of the plan for the main page of their company’s website may question the abilities and creativity of their designer. It is likely that the client would be compelled to begin asking for additions to help this page “pop,” and the designer would find himself in the ridiculous situation of having the client demand to help design the wireframe. And everyone loses. However…

…the design as fully articulated (above) is a different matter entirely. Nice typography, crisp imagery, and consistent theme work to bring this layout together as a compelling design. Very little of what makes this design work could be communicated by a mere wireframe. And if the required detail was articulated by a wireframe, it means that effort was wasted and should have been directed toward crafting the full design for presentation to the client. Again, context matters.

As an anecdote from the above-referenced project, the original plan was to have the branding/nav and promotional areas as centered, distinct “boxes” on the page. In the fully articulated design it became clear that it was much better to have the upper area of the layout be a full-screen–width section rather than discrete, horizontally-limited boxes. This is just one example of how things change when the full design is applied to a wireframe plan.

Wireframes for informational and promotional pages quickly begin to lose their articulate nature, especially where brand-centric issues come into play—and especially when the actual content is not present. It’s highly probable that only the fully-realized design can convey the successful or unsuccessful quality of a page when there is an informational or promotional purpose to the content. This issue is sometimes mitigated when you’ve got the full and exact page content, but why would you then create a wireframe? Communicating promotional information in the context of a brand requires more than gray boxes.

Faulty reasoning and greed

An idea like, “Wireframes will present enough specificity to allow developers to start crafting the functionality, as well as enough context to let the creative team (designers) start to working on visuals,” ignores the fact that information hierarchy is design and is not merely a matter of top-to-bottom or left-to-right order, and that the addition of graphic, typographic, and textural elements can change content relationships, requiring layout changes. Furthermore, if the wireframes are crafted by an information architect (IA) rather than by the designer, design decisions will have been made that may prove faulty later in the design process due to a lack of the IA’s design insight (or foresight). If your client has already signed-off on the wireframes, you could find yourself in a pickle.

So getting a client’s approval of a specific layout and content relationship with the inarticulate boxes appropriate for a wireframe presupposes that the content and the graphic, contrast, and color textures as applied to the content won’t necessitate changing things in order to create a good page viewing/using experience. This is naive at best and irresponsible at worst.

Another instance where wireframes are often inappropriately included in deliverables is when agency bloat and greediness are brought to bear. The common logic is that where a bloated agency charges four times as much as smaller agencies, they’re compelled to offer many times the volume of deliverables in an attempt to represent value. The problem here is clear.

Disappointingly, this approach also typically involves the failed practice of including a scattershot approach to design, where many design options are offered as a matter of course. I’ve discussed that issue already on my blog, but the lesson here is that where you find the one bad behavior, you’re likely to find another other. And another.

Speaking here to companies looking to enlist a Web agency, if your prospective agency describes wireframes as a part of the project deliverables when they don’t yet have a full appreciation of your project, it means they’re working from a script rather than thinking about you. It means you’re talking to the wrong agency.

In conclusion

Before you create a detailed wireframe for any project, ask yourself: “How will this help my design process?” Evaluate your answer carefully before you decide whether or not to craft a wireframe. Actually, I think we’re all in the habit of doing this and most of us intuitively understand how some sort of wireframe will help our process.

Likewise, however, before you create a wireframe for client evaluation and approval, ask yourself: how will this help my client in the project process? Again, evaluate your answer carefully before you decide to craft a wireframe for your client’s evaluation…and before you commit to do so as a part of the project deliverables. Context matters.