It’s Melbourne, Victoria 1998. The state government continues its drive to reduce public waste. Already the bureaucracy has been slashed, utilities and public services privatized, and 16,000 public transport workers put out of their jobs. Tram conductors, affectionately referred to as “connies,” are also out of a job, having been replaced by ticketing machines.[1] This was an efficiency drive on a mass scale. Ticketing machines were assumed to be more efficient and were expected to save the state bucketloads in wages. But the problem was, and still remains, that the machines were not only less efficient than people, they were less effective, too.

Subsequent research into the service offered by Melbourne tram conductors showed what commuters already knew: they did more than just sell tickets. They increased patronage of public transport by making people feel safer. They were far more effective as fare evasion deterrents than random checks by ticket inspectors. They helped passengers alight and they were the “everywhere tour guides.”[2] The people who had thought machines would be cheaper hadn’t understood that customers had a range of needs that were met simply and seamlessly by the conductors.

Businesses typically calculate efficiency by identifying all of the inputs in a process and then weighing them against the cost of delivering the result. This means identifying misuses of resources in order to eliminate the waste or reallocate those resources to better use. Methodologies abound for how to go about doing this, including Kaizen, Six Sigma, Lean, and Scrum. These methodologies produce results for business efficiency but there is also customer efficiency to consider.

Attempts to improve business efficiency can often result in putting effort back onto the customer to fill the resulting gaps in experience. This is where a user-centered design (UCD) approach can address the needs of business and customer efficiency. The UCD process differs by looking closely at customers and then designing for the problems they are experiencing. The tram conductors in Melbourne showed that sometimes you have to look on the ground to witness what is actually happening before you start deploying changes. Otherwise you risk business efficiency colliding with what is efficient and desirable for customers.

Why Efficiency Is Important

Efficiency is key to successful organizations as they look to minimize costs in competitive marketplaces. However, organizations that focus on only their inner workings can easily fail to appreciate the impact that day-to-day operations and internal “efficiency drives” have on their customers.

Customers have their own view of efficiency. This article primarily discusses the customer view of how much of their effort and time is involved in interacting with an organization. Research studies show that customer satisfaction largely depends on this.[3] Design research conducted by Different into the journey of customers along the mortgage process revealed how little patience customers have for their lenders.

Emotions and anxieties escalated when significant customer effort was involved, particularly when the effort was unanticipated. Customers had little tolerance for how long it took the organization to fulfil a transaction or complete a step in the process. But two heroes did emerge from our research. Unlike bank lenders, brokers facilitated and chaperoned their customers, taking on much of their burden. And financial comparison sites were the other customer heroes, as they efficiently reduced the effort of shopping around.

Customers care about service but they do not always understand the inner workings of the organization delivering it enough to fully appreciate the value of the service. What customers do care about is the opportunity cost of the time they put into the service, particularly when they view their time as having been wasted.

Let’s take a step back from efficiency and consider predictability, the topic of the previous article in The 7 Essentials series. For an experience to be predictable, it needs to be intuitive. People have mental models of how they expect an experience to pan out, which they use to predict outcomes. Anything outside of this model requires greater effort from the user. When an experience is unpredictable, people lose their sense of control and trust is diminished, increasing insecurity and making the overall experience feel less reliable. These emotions are more acutely felt when an experience is also inefficient. Efficiency is dependent on adequate predictability, for without it a service or product cannot be used with the optimal amount of effort.

As we have said, how much effort customers expend to complete a task has a direct correlation to their levels of satisfaction. When customers put out greater effort than expected, they become more invested in a successful outcome. If expectations are not met, customers are more likely to experience a cognitive dissonance (an uncomfortable feeling caused by holding conflicting ideas or beliefs simultaneously) and consequently report lower levels of satisfaction than if expectations were correctly set upfront.[4] An inefficient service increases unrewarded effort, pushing the customer toward dissatisfaction. The good news is that customer-centric efficiency for an organization does not mean an injection of new resources to cater for needy customers and confused users. What it does require is an understanding of customers’ goals and expectations to create pathways for them to achieve them.

What Is Efficiency In Experience?

Efficiency in experience can be defined as the degree to which customer effort is facilitated. Every interaction between the customer and an organization’s product or service should happen in the fewest steps possible. In a design or experience context, this simply means that customers who can complete their tasks more quickly and across fewer touchpoints are more efficient.

How far should a business go to mitigate or take on effort on the customer’s behalf? These are tricky questions for self-serve and human-mediated channels alike. The challenges of designing for customer efficiency were outlined by Harvard Business School professor Frances X. Frei, who created a framework to describe customer variability.[5] Frei speaks of:

- Arrival variability: variability in which customers arrive at the point of service.

- Request variability: variance in the types of requests different customers have.

- Capability variability: differences in the skills and competencies of customers.

- Effort variability: differences in the amount of effort customers are willing or able to put in.

- Subjective preference variability: variety in customers’ unique wants and desires.

All of these volatile factors have implications for efficiency, particularly when the customer must actively participate in the interaction. Frei speaks of the trade-off businesses face: do they accommodate variability, or reduce it? Reducing variability means limiting options and attracting price-conscious customers. Accommodating variability means transferring effort to employees to compensate for customer variation. However, this involves higher cost to the organization, which translates to higher cost to consumers.

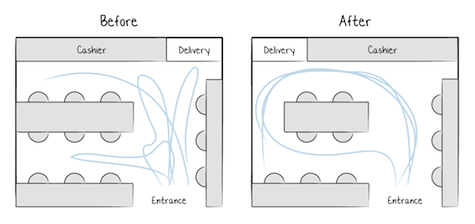

In an experience-design project undertaken by Different for Gomez y Guzman, a Mexican fast food chain, a number of customer efficiencies were introduced into the business that resulted in a sixfold increase in revenue across all store locations.[6] As a result of spatial flow analysis, the store layout was reorganized to optimize the flow of customers queuing, ordering, waiting, and collecting their meals.[7] This addressed the arrival variability factor in Frei’s model.

However, observation and interviews with customers also revealed that half of the ordering time was dedicated to staff educating customers on the menu—a form of capability variability in customers’ knowledge. This factor was not influenced by the organization of the store. As customers ordered, they were asking questions about the food items that were novel to them. (It is worthwhile to note that Mexican cuisine was new in the Australian fast food market at the time).

We addressed the problem through an iterative design process where menu design changes were piloted, benchmarked, and refined. The resulting clear and visual menu facilitated an understanding of the meal combinations available and offered quick suggestions for what to order. Customers learned about Mexican cuisine as they were queuing and were ready to order by the time they reached the counter. As a result, ordering and queuing time was reduced by 50% while volume and sales drastically increased.

The Customer as Co-Producer

Contributing back to the value chain

As more self-service options and platform models (e.g., eBay) emerge, the burden to fulfil transactions switches from the employees within organizations to their customers. The rationale for customer efficiency is is broader than simply facilitating customers’ seamless experiences to complete transactions and derive income. In the Amazon model, the customer provides data in the form of their purchase history and in submitting reviews, which facilitate the process for the next customer. In this case the customer is adding value to the service.[8] The data provided is utilized back into the process. The significance of this cannot be understated. Business efficiency is primarily concerned with the allocation of resources. In the digital realm, customers are able to create brand new resources in the form of intellectual assets that contribute to an increase in customer efficiency.

Customer retention depends on customer effort

The customer is no longer just a patron of a service. The customer is an active participant in co-production, playing a role in his own service provision.[9] Research has shown that the best indicator of retention is customer effort—the burden required of the customer as an active participant in the process.[10] In big business, the quality of an interaction between a customer and the organization is often measured by the Net Promoter Score (NPS). The NPS, calculated through surveying customers on the satisfaction levels of their previous encounter, seeks to provide data on the likelihood of repeat business and advocacy. However, it has been found to be an unreliable indicator of both.

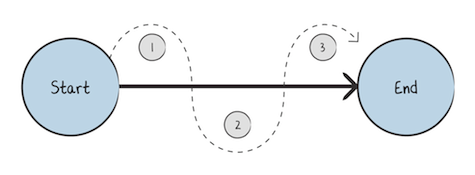

In a study of self-service interactions and call-center efficiency, the most accurate indicator of satisfaction, retention, and advocacy was the amount of effort the customer had to undertake in the process. This included the amount of rework as well as the number of times that customers had to switch channels to resolve or complete an inquiry or purchase. The moments where customer effort is at issue must be identified in order for processes to be optimized. This creates opportunities to accommodate the underlying customer variability and create better customer experiences. Consideration of customer efficiency is vital as it has a direct correlation to satisfaction and advocacy and is the most accurate indicator of future behavior.

How to Achieve Experience Efficiency for Your Organization and for Your Customers

Increasingly, designers are helping organizations understand their customers by conducting research to inform the design of experiences and interactions. This customer research can reveal how the business and customer models might align for the benefit of both.

Businesses must examine their interactions with customers and redesign them to become focussed on saving customer effort. The article Stop Trying to Delight Your Customers (essential reading on customer efficiency) reported that an Australian Internet service provider (ISP) increased its first-point issue resolution rate and reduced calls by 58% by removing productivity metrics from call-center staff performance scores.[11] The emphasis on shorter call times and high-volume call targets is common in call centers as businesses perceive this to be a means of measuring and achieving efficiency. A focus on reducing customer effort to achieve customer efficiency can seem inefficient to businesses if lengths of calls increase. The Australian ISP showed that a renewed focus on the customer experience not only saved customers’ time by reducing the number of calls made to resolve enquiries, it also achieved efficiency for the business.

In examining the potential to alleviate customer effort, organizations must not only consider where they fail their customers but also bear witness to what is really happening. Before changes are designed and deployed, the customer experience must be understood.

The Customer Efficiency Checklist

Questions you should ask about your organization

- Is the business aware of the steps the customer is actually undertaking?

- Are expectations being accurately set upfront, i.e., are customers being presented with the information they need to create corresponding mental models of the experience?

- What parts of the process are inefficient for the customer? What are the underlying causes of inefficiencies?

- Are customers undertaking more steps than necessary? Can any steps be consolidated?

- Where are customers dropping out? Why are these steps deemed more trouble than they’re worth?

- What negative emotions are evoked in the process and how do they affect customer decisions?

- Are steps taking longer than necessary? Can a channel or touchpoint be designed to better satisfy user goals?

- Does the experience move within and across channels without causing rework by the customer (e.g., repeating their query to multiple staff)?

- Is it possible to reward or otherwise motivate customers to take on more effort? Are there unrecognised opportunities for customers to contribute back to the value chain that are not being leveraged?

Once these questions can be answered with the full understanding of the behaviors and motivations of customers the process of designing new experiences can begin.

The Risks of Efficiency

Is it possible to go too far with experience efficiency? Gateway, the computer manufacturer, recognizing a capability gap in its customers, had generous staff levels dedicated to educating buyers on their PC purchases. This was certainly a bid to alleviate customer effort. However, all this accomplished was to upskill shoppers to the point they felt they could shop elsewhere. Interestingly, a decade on, Apple has a similar staff-training-customer model, but Apple’s tightly managed distribution chain and affirming brand shield them from the thrifty.

Banks are now also facing an interesting problem. Branches are more effective at selling products than self-service channels. However customers have embraced ATMs, Internet banking, and online-only accounts to such an extent that loyalty and product cross-selling are being threatened. It is no surprise that big banks are now recognizing this and are recasting their branches as “lounge rooms” to restage service interactions and reinstate the relationship banking model.[12]

There is also the common credo that focusing on efficiency can cause you to miss opportunities for innovation. However, a careful understanding of the customer experience can catch the opportunities for improvement and provide the insights for a potential paradigm shift.

Conclusion

Customers and users are active participants in the service delivery that companies provide. The question for businesses and organizations now is not only how should they drive their own efficiencies, but how should they contribute to the efficiency of their customers’ experiences?

Efficient customers not only spend less of their time and effort, but they also have the potential to contribute back into the value chain when the content and data they provide is repurposed for the company or other users. Efficient customers are proven to be more independent and to demand fewer resources, and they are more loyal and more likely to advocate for the business.

How can you start thinking about customer efficiency to create a customer-centric business? The expectations that customers have when they interact with you must be known. Not fulfilling their mental models and failing to deliver what they expect will result in an unpredictable experience for customers as they exert effort exploring multiple channels just to try and do business with you. Organizations must find out what the capability gaps of their customers are, and go about fixing them in a sincere effort to save customers’ time. The results will be lower operating costs for the business along with more satisfied and loyal customers.

The business case for improving customer efficiency is waiting to be found amongst the experiences of your front-line staff and customers. All you have to do is watch and ask them to know what and where you should be designing.

References

- Martin, L 2008, Time to backtrack on the Connies, The Age, 8 September, viewed 8 June 2011. [back ^]

- The Age 2008, Conductors were never merely ticket dispensers, 15 July, viewed 8 June 2011. [back ^]

- Xue, M & Harker, PT 2002, Customer efficiency: Concept and Its Impact on E-business Management, Journal of Service Research, vol 4, no. 4 253-267. [back ^]

- Cardozo, RN 1965, An experimental study of customer effort, expectation and satisfaction, Journal of Marketing Research, vol. 2, no.3, 244-249. [back ^]

- Frei, FX 2006, Breaking the Trade-off Between Efficiency and Service, Harvard Business Review, vol. 84, 92-101. [back ^]

- Gomez y Guzman, A case study in experience modelling 2010, case study, Different, viewed 8 June 2011. [back ^]

- Bilda, Z 2009, How many seconds does it take to order a burrito: Guzman Y Gomez Case Study, slide show, viewed 8 June 2011. [back ^]

- Xue, M & Harker, PT 2002, Customer efficiency: Concept and Its Impact on E-business Management, Journal of Service Research, vol. 4, 256. [back ^]

- Ibid, 259. [back ^]

- Dixon, M, Freeman, K & Toman, N 2010, Stop Trying to Delight Your Customers, Harvard Business Review, July-August, 118. [back ^]

- Ibid, 121. [back ^]

- Umpqua Unveils New ‘Neighborhood Store’, The Financial brand, viewed 23 June 2011. [back ^]

Illustrations by: Nam Ngyuen